Column

Definitions of Incunabula and Calendars

In general, incunabula are defined as materials that were printed before 1501, using metal type. There are several points to be noted in this definition. Xylographic books (using wooden types) are usually not included in incunabula. Incunabula are not necessarily limited to books. Even today, opinions are divided as to whether or not booklets and pamphlets should be included in the category of books. Broadsides, such as advertisements, however, are included in incunabula if they were printed using metal type, and indulgences and other single-sheet printed items such as calendars are also included in classification. More important for printed material to be considered incunabula is the date of printing. Modern books were subjected to censorship prior to publication, for which reason it has become customary that matters related to their publication (imprints), such as the place and year of publication as well as the name of the publisher, are printed in the books. As for incunabula, however, the year and place of printing and the name of the printer are rarely specified. Thus it has become an important part of incunabula studies to estimate and clarify matters related to the publication, for example, by comparing the types used. For instance, the 42-line Bible, which is owned by the National Library of France and is believed to have been printed by Gutenberg, has no imprint at all. It is considered as an incunabulum, however, because the craftsman who rubricated the 42-line Bible wrote at the end of the Bible that he completed his rubrication work on St. Bartholomew's Day in 1456, and based on this fact, it is concluded that the 42-line Bible had already been printed by 1456. In 1455, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini wrote in a letter that he had seen an advance copy of the 42-line Bible in Frankfurt in the fall of the previous year. From this and other facts, it is believed that the 42-line Bible was printed at some point between 1454 and 1455. As described above, researchers can determine whether certain printed materials are incunabula by gathering information not only from the original material itself by also by pinpointing the printing house through the pieces of type used and estimating the year of printing through information such as the length of operation.

Books printed close to 1500, however, need to be treated with more caution. This is mainly because in the incunabula period, not all cities celebrated the New Year on January 1. Many French cities regarded Easter Day as the beginning of the year. Since Easter is a moveable feast, falling on a certain Sunday in March or April, these cities started the New Year on a different day each year. In Venice, the New Year was celebrated on March 1. In the ancient Roman period, March was the first month of the year. The reason why in the modern calendar the ninth month is called "September" (from the Latin septem meaning seven), the tenth "October" (Latin octo = eight), the eleventh "November" (novem = nine), and the twelfth "December" (decem = ten), is that the modern calendar has taken over the names of the months used in the ancient Roman calendar that began two months later. Florence, meanwhile, celebrated the New Year on March 25. In this city, people regarded the Annunciation, (the day of Jesus Christ's conception) as the beginning of the year. A number of cities celebrated the New Year on Christmas Day. In Byzantine cities, the New Year came around on September 1. Since European cities celebrated the New Year on different days as described above, if it is written in a certain printed material, for example, "printed on February 18, 1500," there is no doubt that it is an incunabulum if it was printed in a city that celebrated the New Year on January 1. But if it was printed in a city that started the year in March or later, it misses being an incunabulum but is rather a post-incunabulum because it was already 1501 in a city that celebrated the New Year on January 1. Usually, in a catalogue of incunabula, if the year of printing for an incunabulum that was printed in a city that celebrated the New Year later than January 1 is written, the year for the city that started the year on January 1 is also added. For example, an incunabulum which indicates "printed in Rome on February 6, 1496" is described as "6 Feb. 1496," but if the incunabulum was printed in Venice, the year of printing would be described as "6 Feb. 1496/97" to show that the year of printing would be 1497 in other cities. If the date of printing is known, the year of printing based on a calendar that started the year on January 1 can be specified, but if the date of printing is unknown, it is impossible to specify the year of printing based on that calendar. Even if it is written in an incunabulum that it was "printed in 1500," the possibility remains that it was actually printed in 1501 depending on which city it was printed in. For example, in 1500, the people of Paris greeted the New Year on April 19, and in 1501, it was April 11. Therefore materials printed in Paris between April 19, 1500 and April 10, 1501 were indicated as "printed in 1500." Printed materials are treated as incunabula if their exact date of printing is not known. If their year of printing based on the calendar that greeted the New Year on January 1 is 1501, they are treated as post-incunabula.

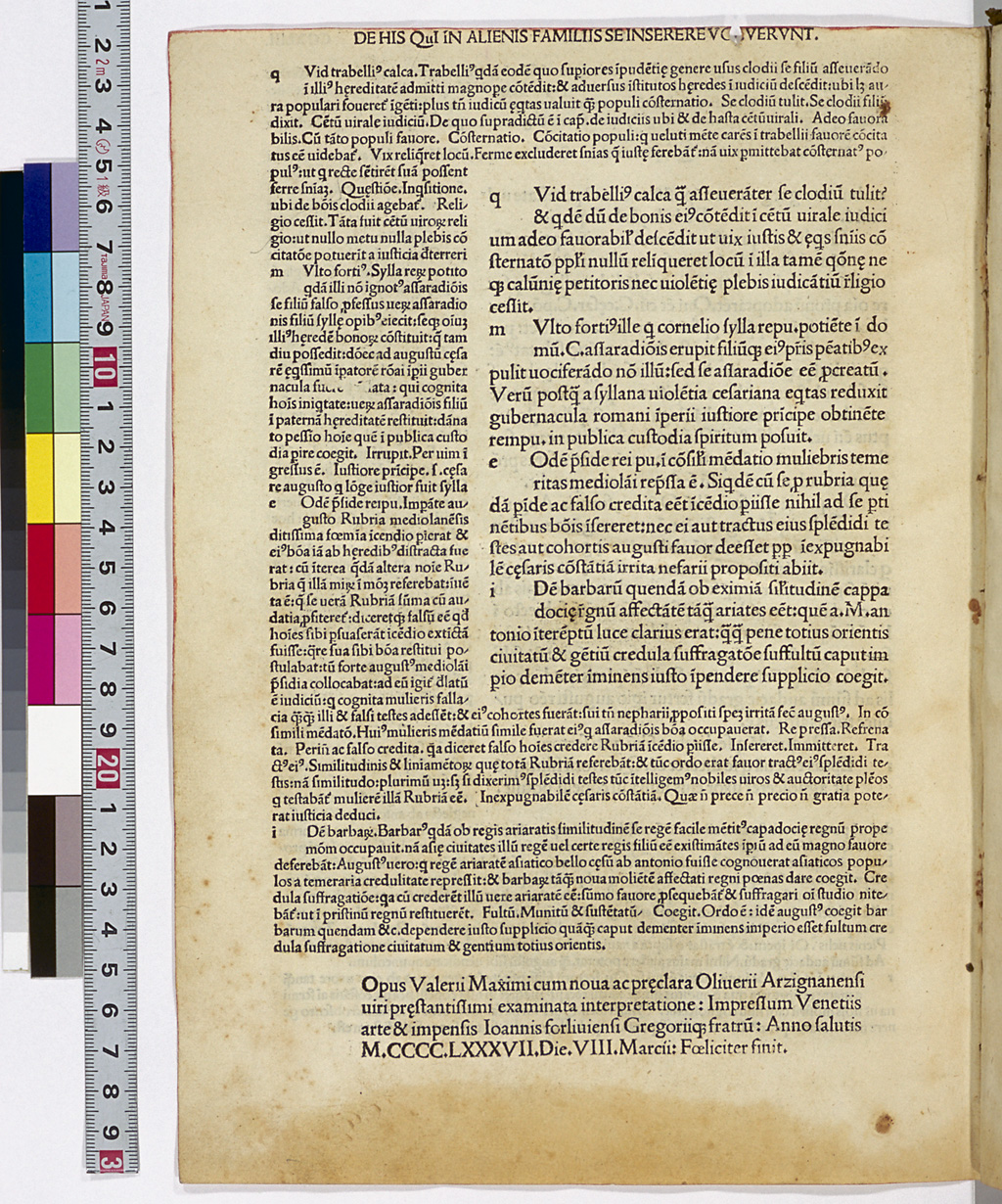

The colophon, which reads in Roman numerals "M.CCCC.LXXXVII.Die.VIII.Marcii," indicates that the book was printed on March 8, 1487.

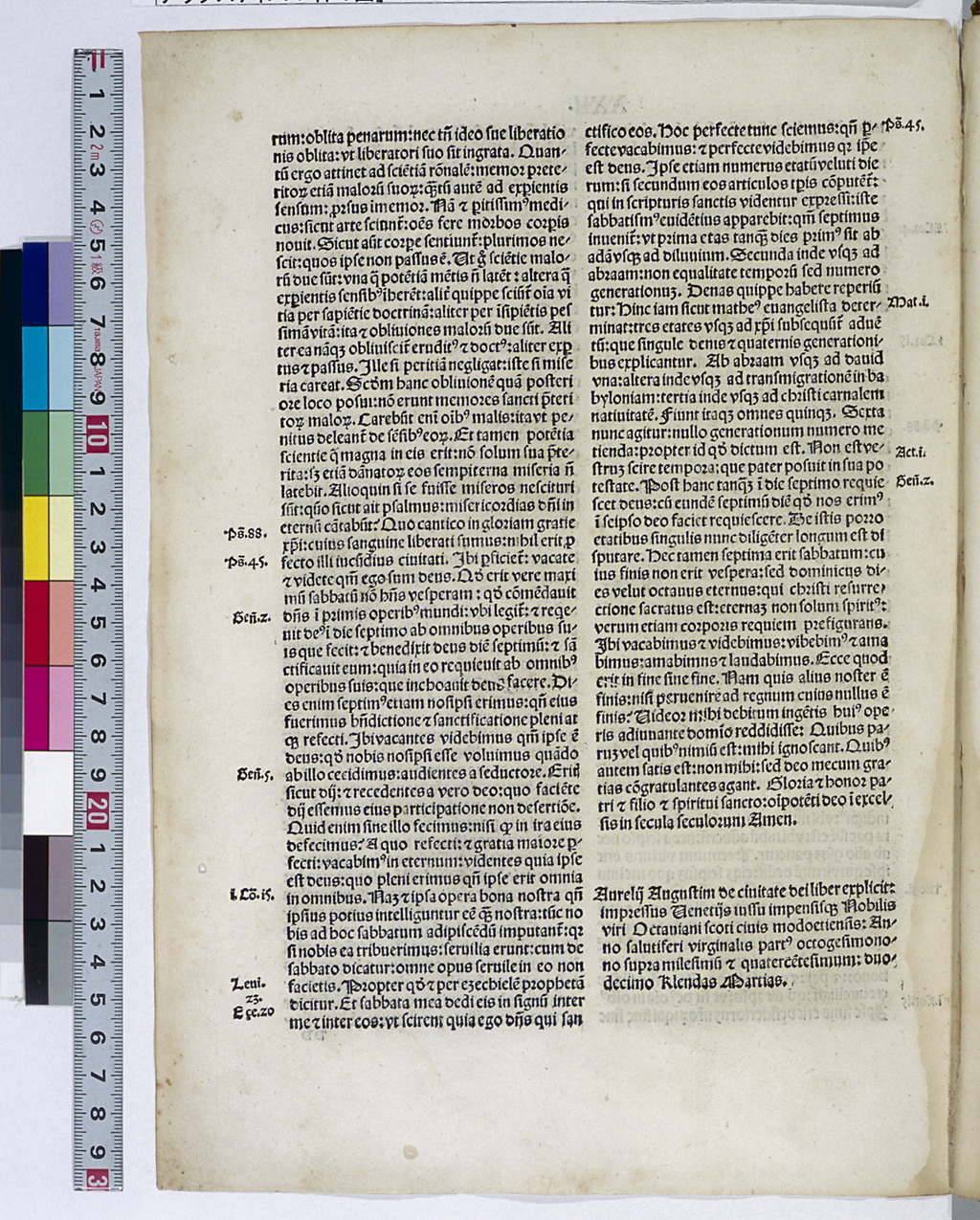

The colophon reads "Anno salutiferi virginalis partum octogesimonono supra milesimu et quatercentesinum: duodecimo Klendas Martias," which indicates "twelve days before the Kalends of March 1489," that is, February 18, 1489. Since the Venetians celebrated the New Year on March 1, this falls on February 18, 1490 in the Julian calendar.

How the dates were expressed in medieval Europe.

In medieval Europe, the Julian calendar, the solar calendar in which one year consisted of 365.25 days, was used as in ancient Rome. The ancient Romans, however, had once used a calendar similar to the lunar calendar, in which each month started approximately on the day of the new moon, and they called the day "kalendae." This word originally meant "proclaim" and the English word "calendar" was derived from it. Christian churches established the ecclesiastical calendar that included various events unique to the religion and created the perpetual calendar or book of hours to make the events known to clergy and believers. A great number of almanacs and books of hours were printed and constitute part of the incunabula. Calendars were written in ancient Roman style with the terminology of the lunar calendar used unchanged. The first day of each month was called "Kalendae," and the 15th day in March, May, July and October (13th day in other months) was called "Idus," which means the day of the full moon. Nine days (nonus) prior to the day of the full moon was the day of the first quarter of the moon, and therefore, the seventh day in March, May, July and October (fifth day in other months) was called "Nonae." These three days served as reference days, and in general, other days were called "a certain number of days before one of the reference days." For example, February 18 in the common year is 12 days before the Kalends (first day) of March (counting inclusively, that is, including the 1st), the next reference day, and therefore, the day was expressed as "ante duodecimo Kalendas Martias." March 11 is five days before the Idus (15th day) of March (including the 15th), the next reference day, and therefore, the day was expressed as "ante quinto Idus Martias."

In many incunabula, the dates are written in this type of complex format, but in the catalogues of incunabula, the dates are usually rewritten in the present style.