Gannen mono – the first overseas emigrants

Eugene M. Van Reed and the first emigrants to Hawaii

A little more than 40 emigrants to Guam, 153 emigrants to Hawaii in 1868 and more than 40 emigrants to California in 1869 were the first Japanese overseas emigrants in a group.

The first emigrants to Hawaii who later came to be called the gannen mono (first year (of Meiji era) arrivals), were recruited by Eugene M. Van Reed, Consul of Hawaii in Yokohama, through employment agents in Keihin area to work mainly as laborers on sugar cane fields. Most of these emigrants were craftspeople and peasants and samurais were also included.

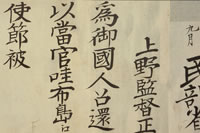

Although Eugene M. Van Reed had received departure permission (passports) for the emigrants from the Shogunate Government, the new Meiji government, however, did not reconfirm the permission and the gannen mono were consequently forced to make their voyage illegally without permission.

The emigrants set sail on board the ship Scioto from Yokohama before dawn on May 17 and arrived at Honolulu Harbor on June 20.

Although the voyage to Honolulu went well, the emigrants faced hardships due to harsh labor conditions in an unfamiliar climate and high prices of commodities after arriving at the plantations. The situation got worse and Tomisaburo Makino, emigrant manager, submitted a petition for rescue to the Japanese Government in December of the same year.

Kagenori Ueno Envoy to Hawaii

The Meiji Government dispatched Kagenori Ueno, director of the Ministry for Civil Affairs, as an envoy in order to resolve the problem. The Ueno party arrived in Hawaii, via San Francisco, on December 27, 1869, and after negotiations with Hawaiian Minister for Foreign Affairs Charles Coffin Harris, came to agree on January 11, 1870 that the 40 emigrants who wished to return to Japan should be returned, and that the rest should be returned to Japan at the expense of the Hawaiian Government after the expiration of their contracts. On March 7, 41 people consisting of the 40 emigrants and 1 child born in Hawaii, arrived in Yokohama, and Makino arrived via a separate vessel on March 26.

This kind of problems frequently occurred in the early stages of emigration to any region thereafter.

Peak years of emigration to Hawaii

Officially contracted emigration

From the problems of the gannen mono onwards, the Meiji Government continually refused requests from Hawaii and other foreign countries for dispatch of emigrants, until 1884, it finally permitted the shipment of emigrants for harvesting pearl oysters in the Torres Strait between the Cape York Peninsula in Northeastern Australia and New Guinea and emigrants to Hawaii the following year. The emigration contracted by the governments of Hawaii and Japan began in January 1885 and the Immigration Treaty between the governments of Japan and Hawaii was concluded in 1886. Under this treaty, approximately 30,000 Japanese emigrants, 26 sets of emigrants in total crossed the ocean. The emigration under the treaty later came to be known as the officially contracted emigration.

Peak of emigration to Hawaii

The officially contracted emigration was discontinued with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1894 and the business of emigration to Hawaii was entrusted to private emigration companies which recruited emigrants and looked after their voyage. Numerous emigration companies, thereafter, were established, including the Kobe Toko Goshi kaisha (Kobe Voyage Partnership Ltd), the Kaigai Toko Kabushiki kaisha (Overseas Voyage Company Ltd) and Makoto Morioka (a sole proprietorship), and they competed with each other to ship emigrants to Hawaii. The recruitment and shipment of emigrants to Hawaii by emigration companies was temporarily banned after the annexation of Hawaii by the United States due to the rise of anti-Japanese nativism on the U.S. mainland in 1899, the emigration, however, resumed in August of 1901 to fill Japanese labor needs in Hawaii when the agreement was reached that assured free immigration. Thereafter until the emigration was restricted by the Gentlemen's Agreement in 1907, Japanese emigration to Hawaii reached its peak and 10 to 25 thousand people crossed the ocean every year.

Five companies and reform movement

During this period, the companies responsible for emigration to Hawaii were the Kaigai Toko Kabushikikaisha (Overseas Voyage Company Limited) (headquartered in Hiroshima), the Tokyo Imin Goshikaisha (Tokyo Emigration Partnership Ltd), the Morioka Shokai (Morioka Company), the Nippon Imin Kaisha (Japan Emigration Company) (headquartered in Kobe) and the Kuamamoto Imin Kaisha (Kumamoto Emigration Company), and they were collectively referred to as the five companies. The five companies colluded with the related Keihin Bank and made enormous profits from the exploitation of emigrants through forced loans and deposits which were claimed in order to prove that the emigrants actually had sufficient money. In May 1905, outraged by the exploitation, Japanese emigrants in Hawaii formed the Kakushin Doshikai (reform fellowship) and ran a protest campaign, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs finally restricted business activities of the emigration companies in Hawaii, as well as prohibited the Keihin Bank from forcing emigrants to deposit their money in it. Most of the bank's employees and the emigration companies’ agents consequently left Hawaii by the spring of 1906.

Shipment of emigrants to other countries and regions

Japanese emigrants were shipped by emigration companies to other countries and regions than Hawaii, including the U.S. mainland, Canada, Australia, New Caledonia, Fiji and the West Indies after the 1880s and Mexico, Peru and the Philippines after the 1890s.

-

Books

-

Huts covered with dried millet stalks in which Japanese emigrants dwelled in the early stages of the officially contracted emigration

Huts covered with dried millet stalks in which Japanese emigrants dwelled in the early stages of the officially contracted emigration -

Female workers of sugar cane fields in the period of the officially contracted emigration

Female workers of sugar cane fields in the period of the officially contracted emigration -

Hotel Fukui (at Yokohama)

Hotel Fukui (at Yokohama)

Failed plans for emigration to Brazil

First Brazil’s attraction of Japanese immigrants

Slavery was abolished in Brazil in May 1888 and consequently, the attraction of immigrants began in Europe in order to secure work force there. In October 1892, Chinese and Japanese immigration was also permitted and Charles Alexander Carlyle, director of the Prado Jordan Company Sao Paulo, traveled to Japan in 1894 to propose the attraction of immigrant laborers to the Yoshisa Imin Kaisha (Yoshisa Emigration Company). Because the Treaty of Amity and Commerce had not yet been concluded between Brazil and Japan, the attraction never came to fruition.

Sho Nemoto of the Colonization Society visited Brazil

A short time after Carlyle's visit to Japan, Sho Nemoto of the Colonization Society visited Guatemala, Nicaragua and Brazil in his capacity as an official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and sent a letter to the Colonization Society reporting that Brazil was a promising county for emigration. At the time the Ministry, however, still took the cautious position that Brazil was not the best country for emigration because emigrants had to work a low-end job (according to the answer given by Saburo Fujii, Director-General of the Trade Bureau, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, during the consideration of the Emigrant Protection Bill in the Imperial Diet in 1896).

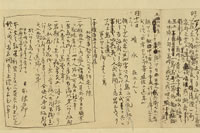

Ship Tosa-maru Incident – the shipment of emigrants to Brazil canceled shortly before departure

In January 1897, the Yoshisa Imin Kaisha (Yoshisa Emigration Company) sent its employee, Chukitsu Aokitsu to Brazil to carry out negotiations with the Prado Jordan Company in order to realize the shipment of emigrants. In May, Aoki sent a telegram confirming the successful conclusion of a provisional agreement, then a formal agreement was concluded between the Toyo Imin Kaisha (Oriental Emigration Company) which had taken over the business of the Yoshisa Imin Kaisha (Yoshisa Emigration Company), and a representative of the Prado Jordan Company in Yokohama and government permission was obtained. Shortly before the departure of the ship Tosa-maru with the first set of 1,500 emigrants on board on August 15, a telegram, however, arrived reporting that due to financial problems the agreement had been cancelled, consequently the emigration was cancelled (So-called the Ship Tosa-maru Incident).

After the Tosa-maru Incident, Sutemi Chinda and Narinori Okoshi, the then former and present Resident Ministers to Brazil, held very negative views on the shipment of Japanese emigrants to Brazil. In November 1897, the Nippon-Imin gaisha (Japan Emigration Company) concluded a provisional agreement with Angelo & C. Fiorita of Rio de Janeiro, and in August 1901, Sanz de Elorz of the same company visited Japan and applied for dispatch of emigrants by emigration companies in various regions, however again, none of these attempts came to fruition. The failure of these negotiations was due, mainly, to emigration policies adopted by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs based on the aforementioned negative views of the Resident Ministers.

-

Books

-

The Guatapara plantation owner's mansion

The Guatapara plantation owner's mansion -

View of coffee plantation in Dumont, São Paulo

View of coffee plantation in Dumont, São Paulo -

Articles in newspapers / magazines

-

A report that the emigration to Brazil was cancelled shortly before the planned departure