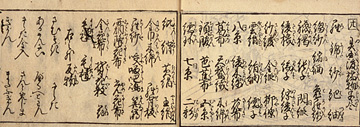

This book is a record of the observations of Mr. Ehara (first name unknown) when he went to Nagasaki. It has illustrations including a map of Deshima. He includes a list of imported cloth, such as beruhetowan, santomejima and korofukuren in his 'Ikoku watari tanmono jitsukushi' (List of the names of cloth from foreign countries).

Home | Part 2: View by Topics | 4. Receiving Knowledge from Overseas (2) Foreign Countries in Daily Life (1)

Part 2: View by Topics

4. Receiving Knowledge from Overseas

(2) Foreign Countries in Daily Life (1)

This chapter introduces the imported goods and images, etc. from the Netherlands that were incorporated into the daily lives of the common people during the Edo period.

Nagasaki: Gateway to Foreign Countries

The culture brought through the trade with the Netherlands were incorporated in a variety of ways into the daily lives of the common people. First, let's look at reports from people who traveled to Nagasaki, which was the gateway to foreign trade.

Saiyu ryodan.

Written and illustrated by Shiba Kokan. S.l.: s.n., 1790. 5 v. in 2. <104-51>

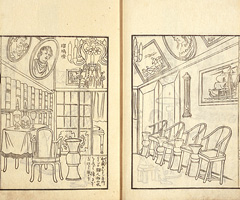

Shiba Kokan visited Nagasaki in 1788. This book is a record of this trip and it includes many illustrations including the chandelier and portraits inside the Dutch factory, to communicate the appearance of Nagasaki and its strong foreign atmosphere.

Nagasaki bunkenroku.

By Hirokawa Kai. Kyoto: Hishiya Magobei, etc., 1818. 5 v. in 3. <139-148>

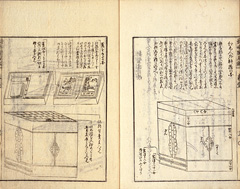

The author, Hirokawa Kai, was a physician in Kyoto. Starting in 1791 he resided twice in Nagasaki for a total of 6 years. This book also introduces coffee and Dutch sweets. The Komojin gekabako no zu (illustrated medical kit of the Dutch) is carefully drawn over 2.5 leaves of paper in particular probably because he was a physician.

Imported Goods from the Netherlands

The trade goods brought by the Dutch ships included raw silk, cloth, sugar, spices, pigments, and leather. These were transported from Nagasaki to Osaka and Edo and brightened up the lives of the people.

Chinese Goods Merchant

Japan had conducted foreign trade with China since ancient times and imported goods were called karamono, tomono, or tobutsu (Chinese things). This did not change even after goods began coming from places other than China including South Asia and Europe.

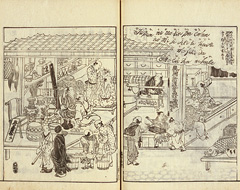

Settsu meisho zue.

By Akisato Rito. Illustrated by Takehara Shunchosai. Naniwa: Morimoto Tasuke, etc., 1796-98. 12 v. <W232-N1>

This shows a Chinese goods merchant in Fushimicho, Osaka (from Vol. 4 Osaka Section) where an electricity demonstration is being given in the back of the room and the shelf on the left is lined with glassware. On the top right of the picture is a comic poem written in the alphabet to give the setting a foreign flavor.

Dutch Products Shown in Store Advertisements

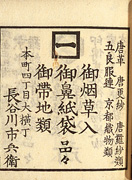

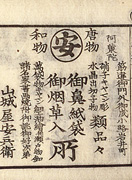

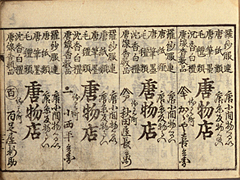

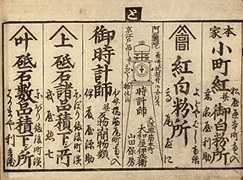

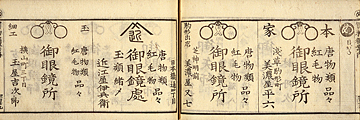

Edo kaimono hitori annai.

Edited by Nakagawa Gorozaemon. Edo: Yamashiroya Sahei, etc., 1824. 3 v. <123-229>

-

This is an advertisement for a satchel shop. You can see the words for Kinkarakawa, imported woolens, and Gorofukuren.

-

This is also an Edo satchel shop, carrying glassware and oil paintings from the Netherlands.

Osaka shoko meikashu.

Osaka: Matsuoka Rihei, 1846. 1 v. <VF6-W4>

-

This is an imported goods store in Osaka, carrying agarwood, sandalwood, and other scented woods.

-

This is a clock shop in Osaka. You can see the word "Oranda (Holland)." As you can see in the illustration, they also carry Japanese clocks, but the watches are luxury import goods from the Netherlands. This book was belonged to a clock merchant Hotta Ryohei who was also a clock document collector.

Cloth

The cloth brought from overseas, such as calico and striped patterns, became so entrenched in Japan that they began to be produced locally.

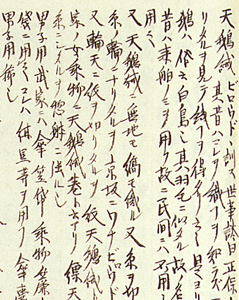

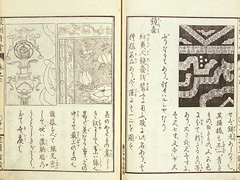

Ransetsu benwaku.

Dutch studies scholar Otsuki Gentaku explains the cloth using Dutch words, such as writing 'gorofukuren' for 'grofgrein' and 'santome' for 'Saint Thomas' (Saint-Thomas is a place name in Coromandel, India). Gorofukuren is a woolen cloth and santome is a striped cloth.

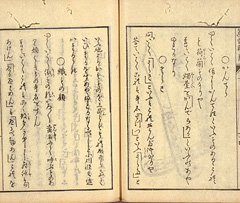

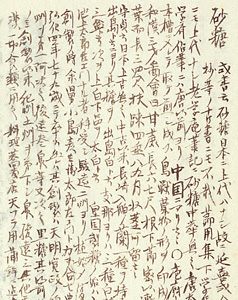

Morisada manko.

Edited by Kitagawa Morisada. Autograph. 29 v. <寄別13-41>

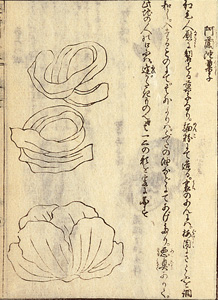

This is an investigative essay on the manners and customs during the Edo period written by Kitagawa Morisada (b.1810). The book contains detailed explanations including observations by the author and illustrations of over 700 items. These images cover foreign-made cloth. For example, for birodo (velvet) it states, "Previously this was only available as an import and was not used by the common people, but today it has come into common use," showing that imported velvet had given way to domestically produced velvet that had come into general use among the common people.

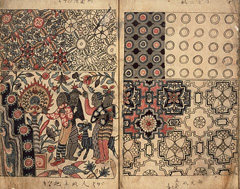

Sarasa (Calico)

This is also written as "kafu," and mainly refers to cotton cloth with hand painted or printed patterns. Calico was imported from India, Java, and Europe and finally was produced in Japan.

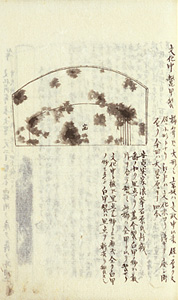

Kowatari sarasa fu.

Ms. 1 v. <わ753-2>

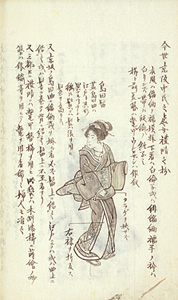

Ukiyo sugata Yoshiwara taizen. Nakanocho e kyaku o okuru nemaki sugata. Kinuginu no wakare.

Illustrated by Keisai Eisen. Edo: Sanoya Kihei, n.d. 1 print: woodcut, col. <寄別2-5-1-2>

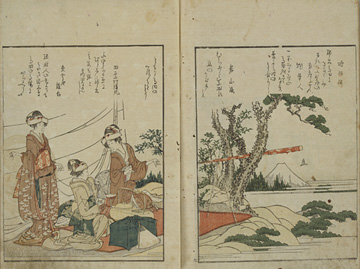

Shima (Stripes)

Shima (stripes) originally meant shima (island), but this name came to mean a woven cloth pattern from islands south of the Japanese archipelago, such as santomejima (also called tozantome or shortened tozan; comes from Saint-Thomas, India) or bengarajima (from Bengal, India). These fabrics came into widespread use among the common people accompanying the popularity of cotton from the mid Edo period and were considered appropriate wear for a chic Edo beauty, and these fabrics often featured in Nishiki-e prints.

Ume no sakigake.

Illustrated by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Edo: Ibaya Senzaburo, n.d. 1 print (3 sheet): woodcut, col. <寄別7-1-1-5>

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) was an Ukiyoe master born to a fabric dyer.He drew a wide variety of stripe patterns including the Shimazoroi onna benkei series and the Taigan joju arigataki shima series, in addition to this work. The various striped kimono are shown on monochrome backgrounds.

Kinkarakawa (Gilded Leather)

Gilded leather is thin tanned and embossed leather with a gilded pattern. It was mainly used as a wall covering in Europe, but in Japan it was a much-prized material used for small items, such as tobacco boxes. In Komo zatsuwa it describes beautiful badminton rackets that used gilded leather on the rim and handle.

Soken kisho.

By Inaba Michitatsu. Naniwa: Onogi Ichibei, etc., 1781. 7 v. <139-209>

This book is about swords and was written by Inaba Michitatsu (1736-1786), a sword accessories merchant in Osaka. Volume 6 contains illustrations of imported leathers and introduces Kinkarakawa. This image shows leather with the portolan chart design used for navigation and a Dutch-made mirror case. It includes the sentiment, "This is such a spectacular thing; there is nothing greater to be found" and "This is extremely beautiful." At the bottom of the left-side illustration of the mirror box is drawn the trademark 'HLM' which are the initials of Hans le Maire (1576-1640), who was a gilded leather craftsman in Amsterdam.

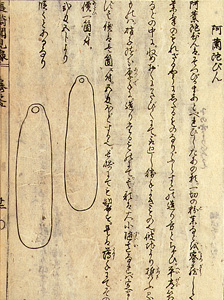

Bekkko (Tortoise Shell)

Tortoise shell, which is the carapace of the hawksbill, a type of sea turtle from the South Seas, was also imported. It was highly prized as a material for handiwork, and was especially popular for women's hair accessories, such as combs and hairpins.

Morisada manko.

Volume 11, which studies the hair styles and clothing of women, also mentions tortoise shell accessories. This image shows a whole tortoise-shell handed down in Morisada's family. It is said that some imitation accessories were made of cow horn or horse hoof or were made with only a thin layer of tortoise shell on the surface. It states, "Tortoise shell combs and hairpins were used on special occasions. For casual clothing, wooden combs gold or silver lacquered and silver hairpins were used, and very few people used tortoise shell accessories," which shows how special tortoise shell accessories were.

Tortoise Shell Works Seen in Pictures of Women

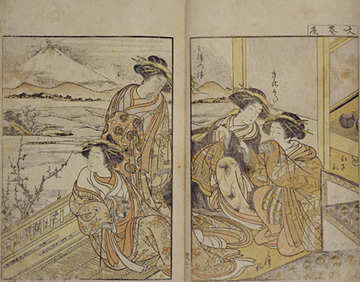

Seiro bijin awase.

Illustrated by Suzuki Harunobu. Edo: Funaki Kasuke, etc., 1770. 5 v. <WA32-5>

Matsubaya uchi yosooi.

Illustrated by Kitagawa Utamaro. Edo: Moriya Jihei, c.1780-1801. 1 print: woodcut, col. <WA33-6>

Ukiyo meijo zue. Toto Shin Yoshiwara yobidashi.

Illustrated by Utagawa Kunisada. Edo: Iseya Rihei, n.d. 1 print: woodcut, col. <寄別7-1-1-2>

This is the beauty by Utagawa Kunisada (the 1st, 1786-1864). A yobidashi is a Yoshiwara top-ranked prostitute. Tortoise shell is very lightweight, but she is wearing so many combs and hairpins in her hair that it makes them look heavy. Her kimono also has a foreign flavor with its stripes and calico strips.

Scented Wood

Scented wood from the south that does not grow in Japan was also an important import good for Japan-Dutch trade. An appreciation of incense-smelling through scented wood burning took hold in the Momoyama period. This reached its zenith in the 18th century and there were many works written about incense-smelling ceremony, and smelling incense was even written about in general books.

Onna setsuyo moji bukuro.

Edited by Yamamoto Tsunechika. Illustrated by Tsukioka Tange. Osaka: Kawachiya Hachibei, etc., 1762. 1 v. <わ370.9-12>

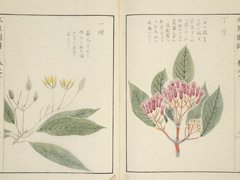

Honzo zuhu.

By Iwasaki Tsunemasa. v.5-8 printed in 1828? , v.9-96: Ms. 92 v. in 12. <寄別9-1-2-1>

This is a leading illustrated botanical book in the Edo period. Volumes 77-81 treat scented wood. This image shows a clove (from Indonesia) and the left page says that is that was brought to Japan by P. F. von Siebold. Belonged to the Shirai Collection (Japanese).

Eyeglasses and Telescopes

|

Lens products, such as eyeglasses and telescopes, were also imported. They eventually were produced domestically, but the advertisements of eyeglass shops continued to use the catch phrase 'Selection of imported foreign goods'. Telescopes were used in observatories for astronomical observations (Kansei rekisho), but they were also used as a visual pleasure. |

Seiro bijin awase sugata kagami.

Illustrated by Kitao Shigemasa and Katsukawa Shunsho. Edo: Yamasaki Kinbei and Tsutaya Juzaburo, 1776. 3 v. in 2. <WA32-4>

Ehon kyoka yama mata yama.

By Oharatei Sumikata. Illustrated by Katsushika Hokusai. Toto: Tsutaya Juzaburo, 1804. 3 v. <寄別5-6-4-5>

Sugar and Sweets

One of the goods most commonly imported from the Netherlands was sugar. In 1702 it was the largest import good by weight with 1.34 million pounds being imported, and in the 1750s sugar accounted for more than 40% of all transactions. It also came to be produced domestically and eventually what had been a luxury good became a flavoring used in sweets and other products and thus became a familiar delight of the common people.

Gozen kashi hiden sho.

Edited by Umemura Ichirobei. Kyoto: Umemura Suigyokudo, 1718. 1 v. <159-74>

This is the first book in Japan on making sweets. It describes many foreign sweets, such as aruheito (from the Portuguese alfelos) and kasuteira (from the Portuguese castella), and also includes rare information on how to make bread in the topic Han shiyo.

Wakan sansai zue.

By Terajima Ryoan. S.l.: s.n., n.d. 81 v. <143-27>

This is an illustrated encyclopedia that was modelled after the Sancai tuhui edited by Wang Qi of Ming China. Under the item 'Manju' (a bean-jam sweet) it states, "The steamed rice bun without the bean jam is eaten once each meal by the Dutch. They call this 'pan' (from the Portuguese pao)". It also uses illustrations to introduce among other sweets kasuteira (castella) and konpeitou (from the Portuguese confeito).

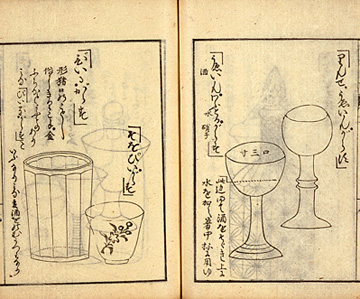

Glass

Glass products, such as those called bidoro (from the Portuguese vidro) and giyaman (from the Dutch diamant), were also originally imported goods. Imported European glass continued to be prized even after the domestic production of glassware became possible.

Saiga shokunin burui.

Illustrated by Tachibana Minko. Edo: Takatsu Isuke, etc., 1784. 2 v. <寄別5-6-4-3>

This consists of illustrations of artisans in 28 occupations, such as carpentry and blacksmithing. This illustration introducing glassblowing states, "Glassware was first brought by the foreigners and then was produced in Nagasaki, but today many glass products are produced in Toto (Edo)." The kimono of the boss appears to be made of calico.

Yukimi hakkei. Seiran.

Illustrated by Utagawa Toyokuni. Edo: Matsumura Tatsuemon, n.d. 1 print : woodcut, col. <寄別2-5-1-2>

Navigation

-

-

-

Study of Japan by

Foreigners Coming to

Japan -

Activities of Dutch Studies

Scholars -

Studying the Dutch

Language -

Receiving Knowledge form

Overseas-

(1) Learning about

Foreign Countries -

(2) Foreign Countries in

Daily Life-

(2) Foreign Countries in

Daily Life (1) -

(2) Foreign Countries in

Daily Life (2)

-

(2) Foreign Countries in

-

(1) Learning about

-

Acceptance of Western

Military Science at the

End of the Edo Period -

Students Studying in the

Netherlands at the End of

the Edo Period

-

Study of Japan by

Copyright © 2009 National Diet Library. Japan. All Rights Reserved