- Kaleidoscope of Books

- Harping about the harp: the Japanese koto and koto music

- Chapter 1: Koto melodies<

Chapter 1: Koto melodies

The NDL’s Historical Recordings Collection* provides access via the NDL website to a wide variety of musical resources. Many of these resources were first available in Japan as 78-rpm recordings.

*For the use of the collection, please refer to How to use this Database.

“Spring Sea”—a world-famous melody

The New Year holiday is a time of the year when the work “Spring Sea,” composed by MIYAGI Michio (1894–1956), is heard throughout Japan. The opening melody of this piece is well known even to people who are not that familiar with koto music. It is scored for koto and shakuhachi, a five-holed, end-blown, bamboo flute.

1) "Haru no umi (Spring Sea).”

Composed by Miyagi Michio, koto by Miyagi Michio, shakuhachi by Yoshida Seifuu. Victor, 1930.12, Product No. 13106.

“Haru no umi" (1) (2)

“Spring Sea” was composed as a duet for shakuhachi and koto in connection with the theme of an Imperial poetry contest held in 1930, which was “a craggy shore.”

The composer, Miyagi Michio, said that “the idea for this work came from the islands of the Seto Inland Sea, and incorporates sounds meant to convey tranquil waves, the paddling of a boat, and the twitter of birds.” It starts with gentle waves washing upon the shore, followed by the shakuhachi singing the idyllic melodies of sea shanties.

When first released, “Haru no umi” attracted little attention. But Renée Chemet (1888–?), a French violinist who visited Japan in 1832, heard this song and arranged the shakuhachi part for violin, which he then premiered together with Miyagi in a performance at the Tokyo Metropolitan Hibiya Public Hall. This concert is depicted in the novel Kesho to Kuchibue [643-56] by KAWABATA Yasunari. Not only was the work well received in Japan, after a recording was released overseas, “Spring Sea” became well-known around the world.

“Rokudan”—a masterpiece of classical koto music

There is a genre of koto music called danmono or shirabemono. These are suites of short, unrelated melodies that are suitable for use as incidental music. The word dan refers to each individual melody, which is fifty-two measures in length when notated in 2/4 time. The convention at the time was for ensembles to play each melody in the suite ad libitum while matching each other’s tempo.

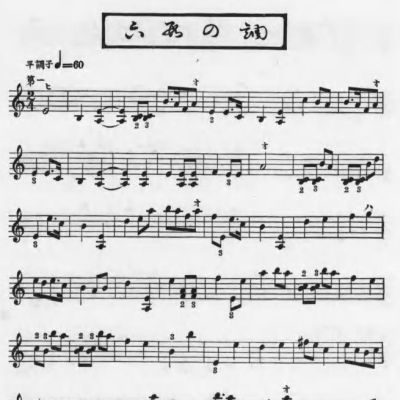

2) “Rokudan”

Composed by Yatsuhashi Kengyou, koto by Miyagi Michio. Victor, Product no. NK-3007.

“Roku-dan” (1) (2)

Also known as “Rokudan no shirabe,” this work consists of six variations of a theme and was long considered to have been composed by Yatsuhashi Kengyou (1614–1685), who was a pioneer of koto music in the Edo period. More recently, however, with the discovery of a manuscript dating from before Yatsuhashi’s birth has called into question the origins of this music.

The motif presented in measures three to six serves as the theme that is gradually developed into six variations.

This work is unusual in that it was written for solo koto rather than as a vocal accompaniment, which was the most typical musical form at the time. It is often taught to beginning koto players and hence has become one of the best-known works for koto. In particular, the motif from the first variation is used in other genres of Japanese music, such as the nagauta “Sukeroku,” which is most often played on the shamisen as well as an ornamentation for melodies in works such as “Sumiyoshi” and “Hototogisu” from the Yamada school of koto music.

It is often said that “koto starts and ends with ‘Roku-dan,’” which is an indication that, although not particularly demanding technically, it is widely performed by both beginners and advanced players.

“Cha-Ondo”—the song of a man and a woman

The impression is strong nowadays that the koto is primarily a solo instrument. During the Heian period (794–1185), however, it was often used by the aristocracy to accompany the singing of songs.

During the 18th century, Edo period musicians increasingly performed music written for shamisen and koto. Additionally, the kokyu and a bowed version of the shamisen, or the shakuhachi were often used in combination with the other two instruments.

A new style of koto music appeared in the first half of the 19th century, in which two vocal sections were separated by an instrumental interlude. Thus koto music developed hand in hand with vocal music.

3) “Chanoyu ondo”

Words by Yokoi Yayu, composed by Kikuoka Kengyou, arranged by Yaezaki Kengyou, shakuhachi by Araki Kodou III, vocals and shamisen by Fukuda Kiku, koto by Kawada Tou, Victor, 1930.8, Product Nos. 51298 and 51299.

“Chanoyu ondo” (1) (2) (3) (4)

Originally, this song was composed Kikuoka Kengyou(1792-1847) as a piece of music for shamisen. Later, Yatsuhashi Kengyou(1776?-1848) added a new koto melody which is different from original one.

This song pertains to the Sado, that is a Japanese tea ceremony. The song lyrics interweave Sado’s elements. for example, tea tools, tea rooms, tea locality. By using some of the words which used in tea ceremony, they express human’s carnal desire.

The song is not only related with tea in the its lyrics, but also the time that needs for preparation is almost the same to length of song, thus it is familiar with tea ceremony as a background music.

By the way, this song is also called “Cha-Ondo” by some schools. “Cha” means tea, “Ondo” means kind of old ritual with regional songs, “Chanoyu” approximately point at the temperature of liquid which used in Sado.

The lyrics of this song extracted from “Onna-temae” which is a piece of old music and it means female style in Sado. In addition, that tune derives from “Ise-Ondo” which indicates Japanese folk song in Ise region. These are the reasons why this song named “Chanoyu ondo” or “Cha-Ondo.”

Next Chapter 2:

Depictions of the koto in pre-modern art