- Kaleidoscope of Books

- The World of Hot Springs Spread from Books

- Chapter 2: Hot springs in literary works

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Hot springs as tojiba (places for recuperation)

- Chapter 2: Hot springs in literary works

- Chapter 3: Overflowing tidbits about hot springs

- Epilogue/References

- Japanese

Chapter 2: Hot springs in literary works

Hot springs have been described in various literary works, such as poems, haikai, novels, essays, and travel writings. They show hot springs, hot spring inns, places and local people through the perspective of the authors of those days. Part 2 introduces such hot springs in literary works.

Hot springs in poems

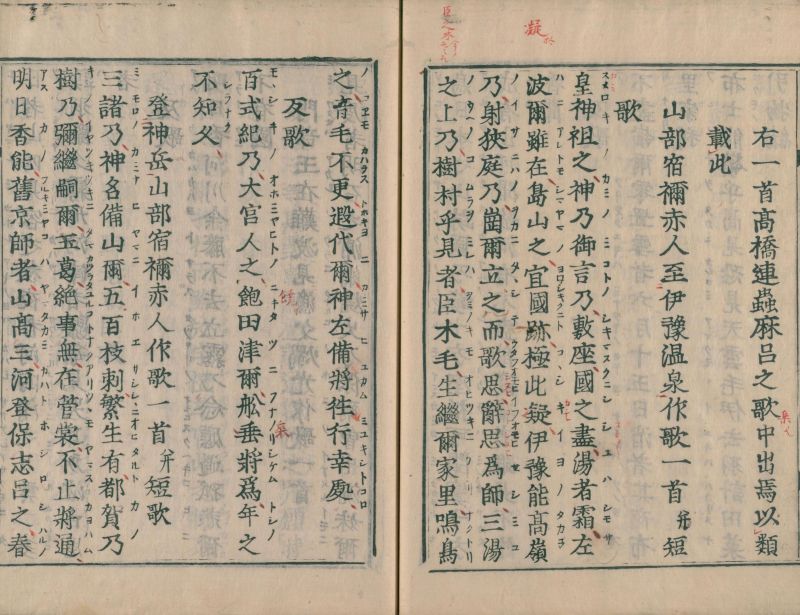

Man’yo shu [WA7-109], which is the oldest extant poetic anthology, includes some poetries concerning hot springs.

For example, when YAMABE no Akahito (years of birth and death unknown) visited Iyo Onsen (now Dogo Onsen), he was reminded that it was the hot spring which emperors had visited, and wrote a choka poem including the name “Iyo.”

OTOMO no Tabito (665-731) stayed at Suita Onsen (now Futsukaichi Onsen in Fukuo-ka Prefecture) and wrote a poem about hearing the cry of a crane.

湯原爾鳴蘆多頭者如吾妹爾戀哉時不定鳴

(Yunohara ni naku ashitadzu wa waga gotoku imo ni koureya toki wakazu naku)

Translation: A crane at Yunohara cries at all times because it is perhaps missing its wife as I am.

In addition, “Tohi,” which is an old name of Yugawara, was included in a local poem from Sagami no kuni.

阿之我利能刀比能可布知爾伊豆流湯能余爾母多欲良爾故呂何伊波奈久爾

(Ashigari no Tohi no kochi ni izuru yu no yonimo tayorani koro ga iwanakuni)

Translation: Not as the hot spring welling up at the riverside of Tohi, in Ashigara, she would never say anything as wavering.

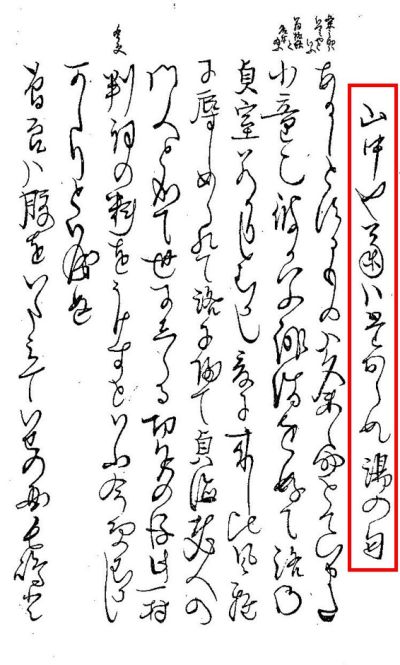

MATSUO Basho (1644-1694), a haikai poet of the Edo period, traveled around Tohoku and Hokuriku with KAWAI Sora (1649-1710) from 1689 to 1691, and returned to Edo. The record of this travel is Oku no hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Deep North) [138-68]. It is written that they visited Yuzen jinja (onsen shrine) for worship and saw Sesshoseki in Nasuyumoto Onsen of Tochigi Prefecture, and that they took a bath and stayed at Izaka Onsen in Fukushima Prefecture. When they visited Yamanaka Onsen in Ishikawa Prefecture, he wrote the following poem, with the words of “Bathing in a hot spring.”

山中や菊はたをらぬ湯の匂

(Yamanaka ya kiku wa taoranu yu no nioi)

When they visited Yudonosan in Yamagata Prefecture, he wrote his impressions on visiting famous mountains in the following poem .

語られぬ湯殿にぬらす袂かな

(Katararenu Yudono ni nurasu tamoto kana)

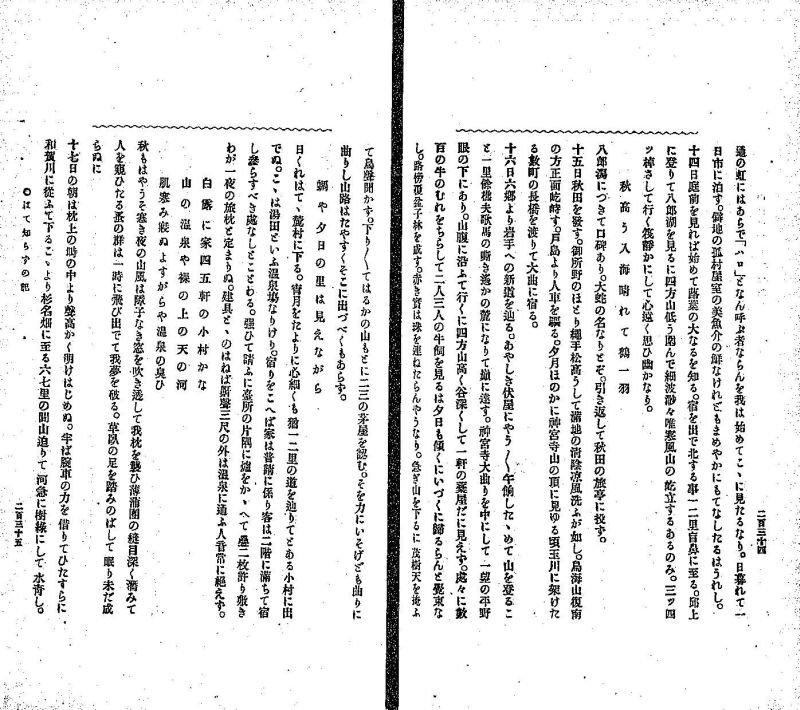

MASAOKA Shiki traveled in Tohoku by foot, tracing the path of Oku no hosomichi in 1893. Its record was published as Hateshirazu no ki (in Dassai shooku haiwa [33-420ハ]) with travel writing and haiku. When he visited Sakunami Onsen in Miyagi Prefecture and Izaka Onsen, and stayed at Yuda onsenkyo in Iwate Prefecture, he wrote the following 3 haiku.

白露に家四五軒の小村かな

(Shiratsuyu ni ie shigoken no komura kana)

山の温泉や裸の上の天の河

(Yama no yu ya hadaka no ue no amanogawa)

肌寒み寝ぬよすがらや温泉の臭ひ

(Hada samumi nenu yosugara ya yu no nioi)

WAKAYAMA Bokusui (1885-1928), a poet who loved traveling and drinking, went on many journeys in his life. From his travel writings and poetic anthologies, it can be read that he visited various hot springs.

Minakami kiko [918.6-W38b] is about his travels in October of 1922 from his home in Numazu City, Shizuoka Prefecture to Nagano, Gunma, and Tochigi. He stopped at Kusatsu Onsen and Hanashiki Onsen, and wrote scenes and made poems. When he heard of the sounds and song of yumomi at Kusatsu Onsen, he wrote 3 tanka including the following.

上野の草津に来り誰も聞く湯揉の唄を聞けばかなしも

Translation: I have come to Kusatsu in Kamitsuke (now Gunma Prefecture). I feel melancholy when I hear the song of yumomi which reaches everyone.

4) Wakayama Bokusui, Yamazakura no uta, published by Shinchosha, 1923. [517-241]

This book is a poetic anthology including tanka which were written during the two years from January 1921 to December 1922, as written in its introduction.

He spent every New Year’s holidays at the inn in Doi Onsen in those days. The master of the inn liked drinking, the same as Bokusui, and they drank together and deepened their friendship. In the beginning of Doi onsen nite from 1922, it is written that he went from the mouth of Kanogawa in Numazu to Doi Onsen in Izu, and then stayed there for about 10 days. This chapter includes about 40 tanka.

湯の宿のしづかなるかもこの土地にめづらしき今朝の寒さにあひて

Translation: The hot spring inn is quiet. It is because of the cold on this morning, which is unusual for this place.

わが泊り三日四日つづき居つきたるこの部屋に見る冬草の山

Translation: My stay is continuing for 3 or 4 days, and mountains covered by winter grasses can be seen from this room, which I have become attached to.

In Yamazakura no uta, there are tanka about hot springs, such as “Shirahone Onsen,” “Yugashima zatsuei,” and “Hatake Onsen nite” besides the above.

Writers of the modern period and hot springs

In the Meiji and Taisho periods, when hot springs had already become very familiar, writers often stayed at hot spring resorts to write, or to heal their ills and wounds. Perhaps because of such experiences, there are not a few works in which hot springs appear.

OZAKI Koyo

Konjikiyasha [79-139] by Ozaki Koyo was intermittently serialized in newspapers from 1897 to 1902, and achieved popularity. It is famous for the scene of separation of Kan’ichi and Omiya, the hero and heroine of the novel, at the seashore in Atami.

It is a voluminous work consisting of zenpen, chuhen, kohen, zokuhen, shokushoku, and shinshoku, but unfinished because of his death. In shokushoku Konjikiyasha, Kan’ichi, who has become a usurer, visits Shiobara Onsen in Tochigi Prefecture. The author had actually visited Shiobara Onsen and stayed at an inn in Hataori, which appears in Konjikiyasha in 1899.

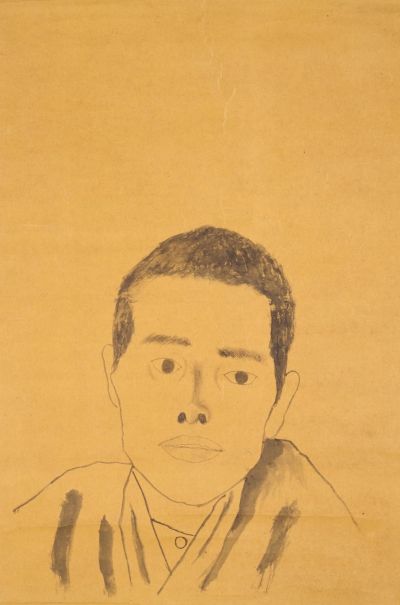

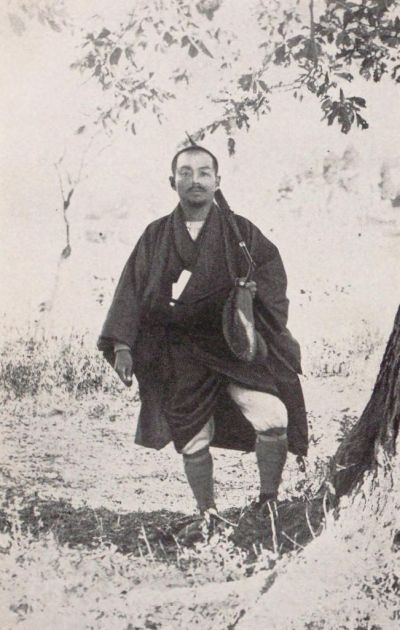

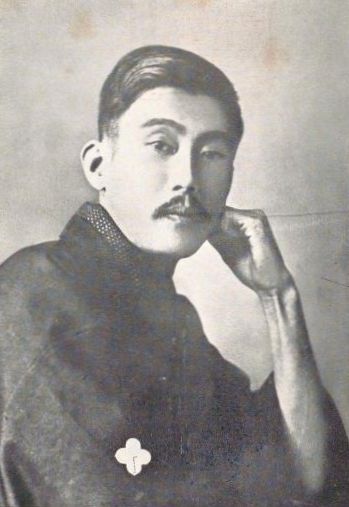

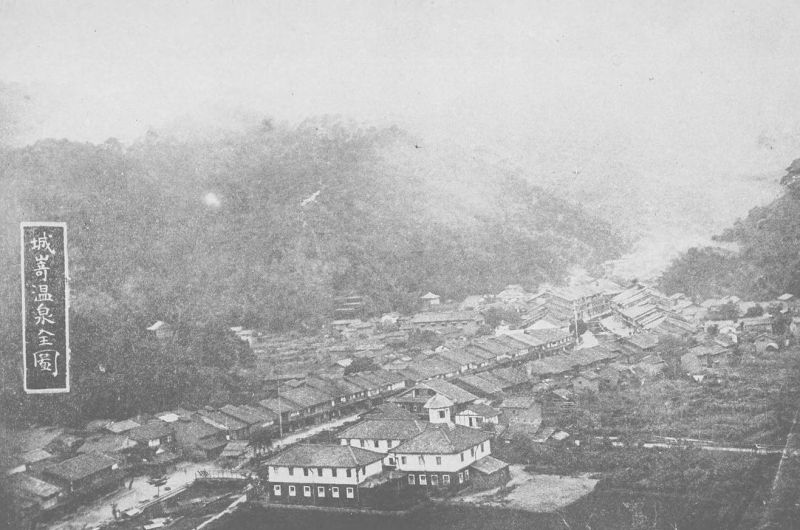

NATSUME Soseki

Natsume Soseki

(photograph from March of 1896, commemorating the graduation ceremony in Matsuyama Middle School)

The hero of Botchan (in Uzurakago [26-375]) arrives in Shikoku as a new math teacher of junior high school, and is so fond of Sumida no Onsen that he goes there almost every day. This is based on the author Natsume Soseki’s experience when he was an English teacher at an Ehime Prefecture junior high school, and it is said that Dogo Onsen in Matsuyama City is the model of the hot spring in the work.

Besides this, the model of Nakoi Onsen, which appears in Kusamakura (in Uzurakago [26-375]) is said to be Oama Onsen, where he stayed when he worked for Fifth High School in Kumamoto Prefeture. In Nihyakutoka (in Uzurakago [26-375]), which was written based on his experience of climbing Mt. Aso with his colleague, he described witty conversations by characters in the inn at Uchinomaki Onsen. His unfinished posthumous work, Meian [KH426-14], is set in Yugawara Onsen, which he visited to cure his rheumatism.

He went into hospital for a gastric ulcer in 1910, and after leaving hospital, went to Shuzenji Onsen in Izu for a change of air. However, he vomited blood there and hovered between life and death. Consequently, he had to be hospitalized again. He wrote about those days in Omoidasu koto nado and Shuzenji nikki [797-500].

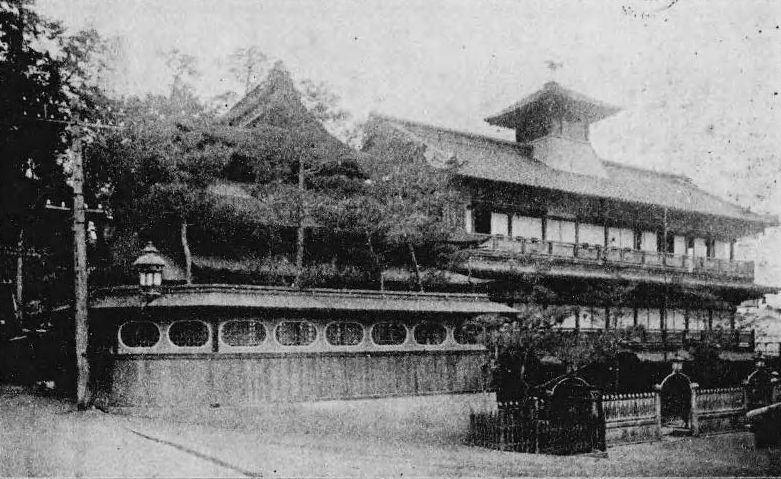

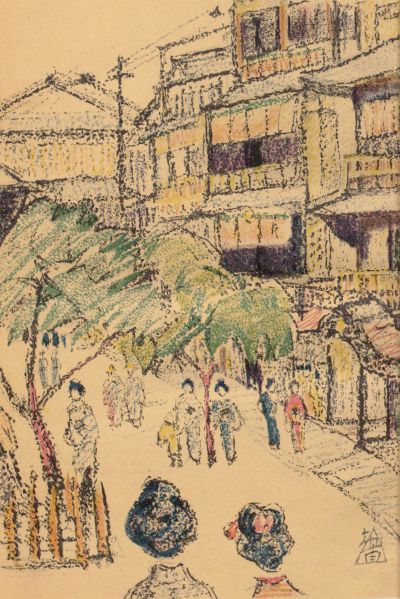

5) TAKAHAMA Kyoshi, Iyo no yu, published by MORI Tomoyuki, 1919. [384-45]

This book was written on the theme of Dogo Onsen by Takahama Kyoshi (1874-1959), who was a haiku poet and novelist. It was edited and published by Mori Tomoyuki, the mayor of Dogoyunomachi (now Matsuyama City, Ehime Prefecture), where Dogo Onsen was located. In addition to five essays such as “Setonaikai” and “Yugeta no kazu,” it consists of illustrations by a Western style painter, SHIOTSUKI Toho (1886-1954), and haiku written by Kyoshi and his master, Masaoka Shiki.

The passage “Natsume Soseki” is an essay in which Kyoshi described Soseki, then a teacher of Matsuyama Middle School.

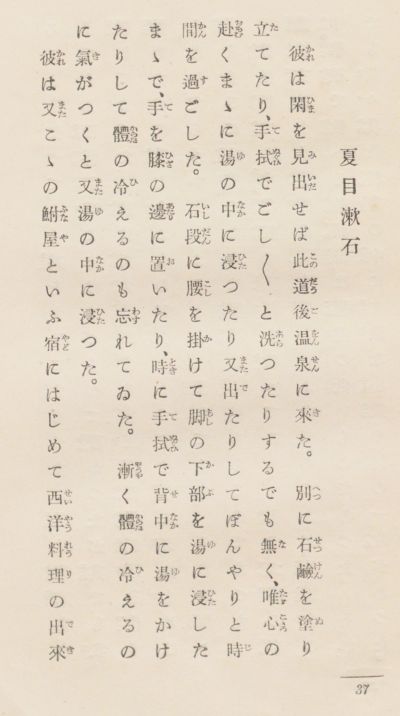

「彼は閑を見出せば此道後温泉に来た。別に石鹸を塗り立てたり、手拭でごしごしと洗ったりするでも無く、唯心の赴くままに湯の中に浸ったり又出たりしてぼんやりと時間を過ごした。(He came to Dogo Onsen if he had time. He spent his time leisurely lounging in the hot spring and coming out of it only as he would do, without applying soap to his body or washing with a towel.)」

「彼は早く此地を去り度いと思ふことも一再では無かったが、彼を此の地から引き離し兼ねるものに唯一つの道後温泉があった。彼は学校をすませて帰ると手拭を手にして早速此の温泉に出掛けた。(He thought not a few times that he wanted to leave here, but he could not leave here because of Dogo Onsen. He went to it bringing a towel as soon as he came from school.)」

These descriptions of Soseki remind us of the experiences which he wrote in Botchan himself. They tell us how much he loved Dogo Onsen and how often he went there.

SHIGA Naoya

Shiga Naoya's short story “Kinosaki nite” (in Yoru no hikari [377-23]) is set in Kinosaki Onsen in Hyogo Prefecture as the title shows. It was written based on his experience of having a train accident and staying there in order to recuperate his wounds. It is a psychological novel about life and death through the deaths of small animals the hero sees in the hot spring resort.

Kinosaki Onsen also appears in An’yakoro (in Shiga Naoya zenshu [913.6-Si283s2]) later. In addition, Yajima Ryudo [913.6-Si283h] is set in Kusatsu Onsen, and Honen-mushi [913.6-Si283h] is set in Togura Onsen in Nagano Prefecture.

KAWABATA Yasunari

In an essay called “Yugashima Onsen” (in Izu no tabi [KH851-L1992]), Kawabata Yasunari (1899-1972) wrote the following.

「伊豆の温泉はたいてい知っている。山の湯としては湯ケ島が一番いいと思う。(I know most hot springs in Izu. I think Yugashima is the best of the ones in the mountains.)」

「私は温泉にひたるのが何よりの楽しみだ。一生温泉場から温泉場へ渡り歩いて暮したいと思っている。(I enjoy bathing in hot springs more than anything else. I would like to live going from hot spring to hot spring for the rest of my life.)」

He visited Izu for the first time in 1918, when he was a student of First High School. The experience of meeting a beautiful traveling dancer who was a member of a group of traveling entertainers at an inn and traveling with them in Minami-Izu became the basis of the novel Izu no Odoriko [551-265]. In the story, the hero travels from Yugashima Onsen to Shimoda after crossing Amagi Pass and staying at Yugano Onsen.

From this point on, Kawabata began to visit Yugashima Onsen frequently. He wrote a novel while staying there. In “Izu no odoriko no sotei sonota” (in Izu no tabi [KH851-L1992]), he wrote about proofreading Izu no odoriko with KAJII Motojiro (1901-1932) at Yugashima Onsen.

His novel Yukiguni [KH254-H5] was set in Echigo Yuzawa Onsen, and he visited and stayed there several times since 1934 to write.

Travels to hot springs

Some writers described hot springs in travel writings, travel reports, or essays which summarize their experiences on their travels.

OMACHI Keigetsu (1869-1925) was a poet who loved traveling. He wrote about various local hot springs in his travel writings, such as Kaga no Yamanaka onsen [29-228] , and Kinosaki onsen no shichinichi [96-493].

The hot spring with which he was the most familiar was Tsuta Onsen in Towada City, Aomori Prefecture. He visited it for the first time in 1908 in order to write a travel piece, and toured Oirase Gorge, Tsuta Onsen, Lake Towada, and so on. The travel writing was published as “Ou isshuki” in the magazine Taiyo, and later issued as Towadako (in Kounryusui [94-616]) . He often visited Tsuta Onsen afterwards, and finally transferred his legal domicile to it in his last years (Kindai bungaku kenkyu sosho, vol.24, edited by Showajoshi daigaku kindai bungaku kenkyushitsu. [910.26-Sy961k]).

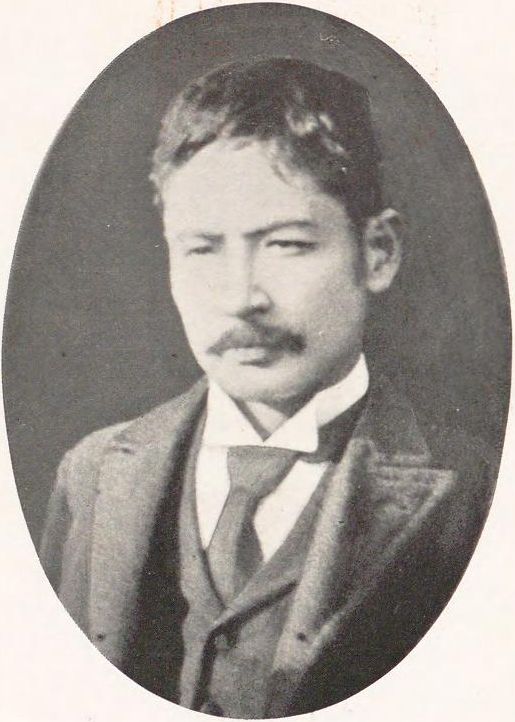

The novelist TAYAMA Katai (1872-1930), who was famous for Futon [26-455] and Inaka kyoshi [329-15], also wrote many travel writings. Especially, he traveled all over Japan to visit hot springs. There are works featuring hot springs themselves in his writings such as Onsen shuyu [394-232], which is introduced below, Onsen meguri [KH612-H297], and Ikaho annai [590-317], which was written at the request of the Ikaho kosen jimusho.

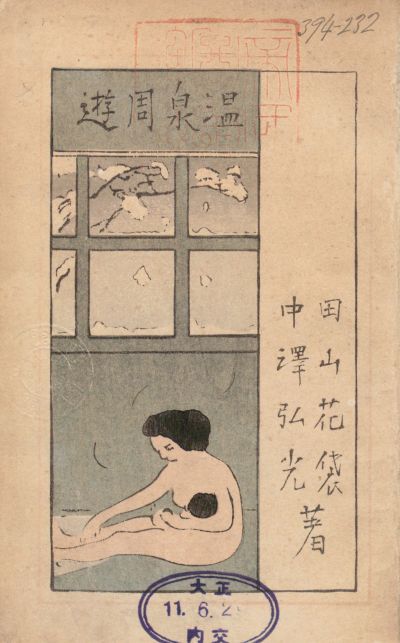

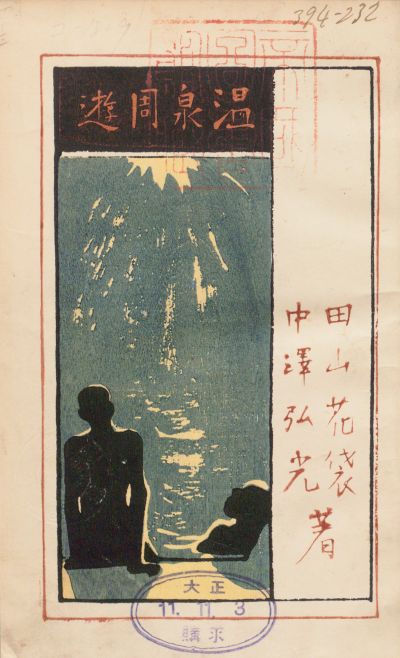

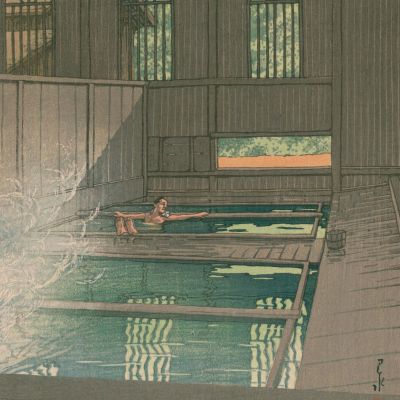

6) Tayama Katai, Onsen shuyu, illustrated by NAKAZAWA Hiromitsu, published by Kinseido, 1922. [394-232] Higashi no maki, Nishi no maki

This book is divided into two volumes; Higashi no maki covers from the Kanto plain to Tohoku region, and Nishi no maki covers from Hakone to Kyushu. There are illustrations of various hot springs by Nakazawa Hiromitsu in the first half of each volume. It is also valuable for learning about the manners and customs of hot springs in those days from the Meiji to Taisho periods.

His narrative is very free and not just uniformly admiring. However, as he edited Shinsen meisho chishi [72-432] published by Hakubunkan, he often expressed his admiration for natural scenery frankly. There are also contents in this book such as a geography on the way to the hot springs, a description of the hot water at each hot spring, impressions of the city, and literary background.

For example, in “Hakone” at the beginning of Nishi no maki, he wrote the following in comparison to his previous visit.

「箱根は電車が出来てから全く勝手が違つて了つた。山も別の山だ。渓流も別の渓流だ。さういふ気がした(Hakone has had a completely different feel to it since the train was built. The mountain is another mountain. The stream is another stream. That's how I felt.)」

He also described the new scenery seen from the train, one scenic point after another, as follows.

「電車で行くと、あの賑やかな中にも、昔の街道筋の温泉場らしい気分の残つてゐる湯本も、(中略)何も彼も下に見くだして、そして一直線に高い高い強羅(がうら)公園へと行つて了ふのであつた(The train looks down on everything, including the lively town Yumoto, which still retains the feeling of a hot spring on the old road. Then, it goes straight to the high, high Gora Park.)」

Next Chapter 3:

Overflowing tidbits about hot springs