![]()

Chapter 1: Literature

Section 2: Translated French literature

The first French literature work translated into Japanese from the original French was Jules Verne's (1828-1905) Around the World in Eighty Days translated by KAWASHIMA Chūnosuke (1853-1938) in 1878. Thereafter a variety of works were translated from both the originals and English translations, including popular literature by the likes of Dumas father and son (father 1802-1870, son 1824-1895) and Victor-Marie Hugo (1802-1885), and naturalism literature by Émile Zola (1840-1902) and Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893), and became widely popular. However, at times these translations greatly abridged the originals, changed the character names to Japanese ones and changed the setting to Japan, making many of them more proper to be called adaptations (rough adaptations) rather than translations. It can be seen that the translators repeated trials and errors to attempt to convey to the readers the stories of other countries, with which they were little familiar at the time, without losing the purport and effect of the originals.

The beginnings of translation

Jules Verne, KAWASHIMA Chūnosuke (Tr.), Hachijūnichikan sekai isshū, KAWASHIMA Chūnosuke, 1880 [26-212]

This is the first translation of Jules Verne's Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (Around the World in Eighty Days) and was the first translation of a literary work from the original French directly into Japanese. Translator KAWASHIMA Chūnosuke utilized the French that he learned at the Yokosuka Shipyards, and worked as an interpreter at Tomioka Silk Mill and other locations, and later made a living as a banker. When KAWASHIMA visited the United States as the interpreter for a mission seeking to sell silk, he purchased an English translation of the work, and using it as reference, began work on the translation of the French original using a copy he had already obtained in Japan. After returning to Japan, he published the first part at his own expense from Keio Gijuku Press, only 5 years after the publication of the original. The first part was well received, resulting in the second part being published by the same publisher who paid the publishing expenses. Readers of the work learned about the diversity of the world from the depictions of the various lands visited by the main character Phileas Fogg, and took in the sense of values of the time that countries which possessed better technologies, wealth and military strength were superior. A large number of Verne's works were also translated after the success of this work.

Dumas father and son

SEKI Naohiko (Tr.), Seiyō fukushū kidan 1, Kinkōdō, 1887 [23-31]

This is the first translation of Le Comte de Monte-Cristo (The Count of Monte Cristo), one of the most important works of Alexandre Dumas (father). The translator, SEKI Naohiko (1857-1934), was a reporter for the Tōkyō Nichinichi Shinbun newspaper at the time, and later worked as a lawyer and a politician. Although the original work, which is a great work consisting of 117 chapters, tells the story of main character Edmond Dantès who is accused of a crime he did not commit, and after escaping from prison, obtains a treasure and seeks his revenge under the alias of the "Count of Monte Cristo", this translation ends with chapter 13 in which Dantès is imprisoned. It is suggested at the end of the book that there would be a conclusion to the story, but it seems to have never been published. A large number of Dumas' (father) other works were also translated, including Les Trois Mousquetaires (The Three Musketeers).

Seisei koji and Tenkō itsushi, Shinpen tasogare nikki, Shinshindō, 1885 [特41-991]

This is a translation of La Dame aux camélias (The Lady of the Camellias) (1848), one of the early long form novels of Alexandre Dumas (son), the translator of which is journalist and literati KOMIYAMA Keisuke (Seiseikoji, Tenko, 1855-1930). The original work tells the story of courtesan Marguerite Gautier, nicknamed "Tsubakihime (the lady of the camellias)" who meets the unsophisticated youth Armand Duval and finds true love; however she is forced to part from him and finally died an unhappy death. This translation is an adaptation, as noted in the foreword, "The work has been adapted by setting the story in Japan for ease of understanding", and the characters were renamed using Japanese names, such as Marguerite Gautier as "Haru" and Armand Duval, "MINASE Seinojo". The scenes in the illustrations were depicted in a Japanese style.

Alexandre Dumas, KATŌ Shihō (Tr.), Tsubaki no hanataba, Shun’yōdō, 1889 [特11-275]

This work is a translation of La Dame aux camélias (The Lady of the Camellias) published in book form after it was serialized in the magazine Shosetsu Suikin. The translator is KATO Shiho (1856-1923) who was a journalist for the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, and in the same newspaper also serialized the first translation of Dumas' (father) Les Trois Mousquetaires (The Three Musketeers) as San'nin Jusotsu. In this translation, the characters are given Japanized names, with Marguerite Gautier as "Marugariito" and Armand Duval as "Aruman", but the setting remains France. Marguerite Gautier, who always wears camellia flowers and is given the nickname "the lady of the camellias", which is here translated as "Tsubakimusume", with the more common translation of "Tsubakihime" not becoming established until the publication of OSADA Shuto's (1871-1915) translation Tsubakihime [新別つ-2] in 1903. There are many different translations of this work, and it was the only work of Dumas (son) that was widely popular in Japan.

Émile Zola and naturalism

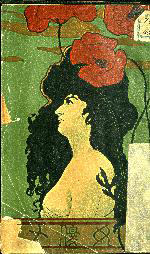

[Emile Edouard Charles Antoine Zola], NAGAI Kafū (Tr.), Joyū Nana, Shinseisha, 1903 [78-42]

This is a collection consisting of an abridged translation of Émile Zola's long form novel Nana and a translation of his short novel L’Inondation as well as the critique Emīru Zora to Sono Shōsetsu (lit. Émile Zola and his novels) translated by NAGAI Kafu and was published as Volume 1 of the 19th Century Literature Collection. The cover art by Japanese style painter HIRAFUKU Hyakusui (1877-1933) depicts an image of a woman which gives the impression of Nana. Nana tells the raw story of the life of stage actress Nana as she became a courtesan and used her physical appeal to ruin upper class men, until Nana herself also died young. Zola was considered as one of the leading authors in France's naturalism literature. During this period, Kafu released a series of works strongly influenced by Zola, building his position as a writer. Zola's methodology also had an influence on KOSUGI Tengai (1865-1952) and TAYAMA Katai (1872-1930) , and played a role in the establishment of naturalism literature in Japan.

Translation of Les Misérables

Victor Marie Hugo, KUROIWA Ruikō (Tr.), Ā mujō, Husōdō, 1906 [26-371]

This is a translation of Victor-Marie Hugo's Les Misérables by KUROIWA Ruiko (1862-1920) who launched Yorozu Chōhō [新-515]. Ruiko felt that an appealing serial was needed to increase the number of newspaper readers, and serialized this novel from October 1902 to August of the following year and then published it in 2 volumes in 1906. In this adaptation, Ruiko, who focused more on ease of reading than accuracy of translation, made major changes to the composition and expressions used in the details in order to make them more suited to Japanese tastes maintaining the main plot of the original, and this style called "Ruiko-mono" proved extremely popular with readers. This is the story of Jean Valjean, who was imprisoned for 19 years for the crime of stealing a single loaf of bread, reformed himself after being released, and lived a stormy life. The brilliant free translation of the title Ā mujō (lit. Oh, misery!), together with Gankutsuō (lit. "King of the Rocks", The Count of Monte Cristo) also by Ruiko, had a major influence on later translations.

TOKUDA Shūsei (Tr.&Ed.), Aishi, Shinchōsha, 1914 [340-46-(3)]

This is a translation of Les Misérables by novelist TOKUDA Shusei (1871-1943) published as Volume 3 of Seiyō taicho monogatari sōsho (lit. Western Epic of Romance Series) by Shinchosha. As noted in the series explanation at the beginning of the book, "We have abridged long works and provided them as palm-sized booklets. We have taken pains to ensure not only that the story summary is understood, but that the atmosphere of the originals is also conveyed.", this is a series of abridged translations. In 1918 this work was retitled Aishi monogatari (lit. Sad History) [31-740] and republished. Les Misérables has proved continuously popular since its initial translation in 1887 to today, and has been published in a number of different translations.

Pierre Loti's visit to Japan

Pierre Loti, IIDA Kirō (Tr.), Okame hachimoku, Shun’yōdō, 1895 [45-277]

Pierre Loti (real name, Julien Viaud, 1850-1923) travelled around the world as a naval officer in the dozens of years between graduating the Naval Academy and retiring from service, and authored a number of works based on his experiences. The original work Japoneries d'automne (Japan in Autumn) is a collection of essays from Loti's time spent in Japan in 1885. This text consists of several pieces from the original which IIDA Kiken (1866-1938) translated, and was published including the Edo no butōkai (lit. A Ball in Edo), which was serialized in Fujo zasshi [雑51-61] in 1892, and several other pieces. This title of the work, Okame hachimoku (lit. Bystander's Vantage), was based on the viewpoint of Loti, as a foreigner, and is a very loose translation with Kiken's views intermixed. Edo no butōkai (lit. A Ball in Edo), which describes the experience of the ball held for the Emperor's Birthday at the Rokumeikan (lit. Deer Cry Pavilion) in November 1885, is a valuable record which scrupulously describes one aspect of Meiji Enlightenment. AKUTAGAWA Ryunosuke (1892-1927) had Loti appear as a character in the short story Butōkai (lit. The Ball).

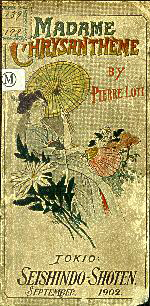

[Pierre Loti], TSUTSUI Jun (Ed.), Okiku fujin, Seishindō shoten, 1902 [139-198(洋)]

This is the first translation of Loti's Madame Chrysanthème. The model for "Kiku" was "Kane", a Japanese girl with whom Loti lived together in Nagasaki when he first came to Japan in 1885. This work written in a diary style describes Japan and Kiku as seen from Loti's point of view. While this became a best seller in France, riding a wave of Japonisme, the depictions by Loti, who never questioned the superiority of western civilization, are at times so severe that it was also criticized for being prejudiced against Japan.

This work is a reading book for English students and contains an annotated English version and its Japanese translation. The content is extremely abridged and none of the negative expressions regarding Japan are present.

Children's literature

François de Salignac de La Mothe- Fènelon, MIYAJIMA Harumatsu (Tr.), Teremaku kafuku monogatari, Daiseidō, 1879-80 [特40-617] 】

This is the first translation of Archbishop François de Salignac de La Mothe Fénelon's (1651-1715) Les Aventures de Télémaque (The Adventures of Telemachus) and is one of the earliest examples of French literature translated into Japanese. The translator was MIYAJIMA Harumatsu (1848-1904) who engaged in translating French books on military strategy and other fields, as a government official, and the publication ended at the eighth volume which was a little less than one third of the total length. The original written as an educational material for Louis, Duke of Burgundy (1682-1712), the nephew of Louis XIV (1638-1715), is a story based on Homer's Odyssey in which the main character Télémaque (Telemachus), having lots of adventures in the company of the goddess Minerva (Athena) who poses as Mentor, a friend of Telemachus's father Ulysses (Odysseus) learns the concept of the ideal sovereign. In this translation, Telemachus is written as "Teremaku", Ulysses as "Yurisu" and Mentor as "Mantoru", and the scenes in illustrations are depicted in Japanese style.

Marie Le Prince de Beaumont et al, INOUE Kan’ichi and YANO Ryūkei (Tr.), Seiyō senkyō kidan, Toyodo, 1896 [68-403]

This is a collection of translated fairy tales by French authors focusing around poet and writer of fairy tales Charles Perrault's (1628-1703) Histoires ou contes du temps passé avec des moralités (Stories from Past Times with Morals) together with Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve (c. 1695-1755) and Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont (1711-1780) and other authors. From Perrault's fairy tale collection, the first translations of 3 works, Aohige (Bluebeard), Suibijin (Sleeping Beauty), and Byokun (Puss in Boots), and also Fusubori (Cinderella) are included. Japanese style illustrations by YAMAMOTO Shoun (1870-1965) bring a unique, semi-western impression to the tales from another country. In one scene of Suibijin (Sleeping Beauty), a young nobleman sees the princess asleep on a beautiful bed; however, the depicted clothing and furniture are all in Japanese style.

Jules Verne, MORITA Shiken (Tr.), Jūgo shōnen, Hakubunkan, 1896 [74-24]

This is the first translation of Jules Verne's novel Deux ans de vacances (Two Years' Vacation) which tells the story of 15 boys stranded on a desert island, and the adventurous lives they lead there for two years, serialized in Shōnen Sekai [Z32-B239] in 1896 and published in book form. The translator, MORITA Shiken (1861-1897), was a journalist for the Yūbin Hōchi Shinbun newspaper who became popular after returning to Japan from a tour of Europe and America in 1886 and releasing translated novels one after another in the popular novel section of this paper and in magazines. This work is one of the prime examples of these works and is a retranslation of English translation. Shiken was known as the "King of Translators" and wrote in a unique style, called the "careful style" with the rhythm of classical Chinese writing, while still aiming to remain as faithful to the intent of the original as possible when translating, and had influence on the world of translation of literature which more often featured bold changes and adaptations at the time.

Hector Henri Malot, KIKUCHI Yuhō (Tr.), Ienakiko, Shun’yōdō, 1912 [329-128]

This is a translation of Hector Malot's (1830-1907) Sans famille by novelist and Ōsaka Mainichi Shinbun newspaper journalist KIKUCHI Yuho (1870-1947). It was published as one of the family-oriented story series that Yuho serialized in the newspaper, and was well received. The work is not a verbatim translation, but the content is recreated mostly faithful to the original. Thereafter, the work became popular in Japan under the title Ie Naki Ko (lit. the boy with no home). The story tells the tale of a boy Rémi who is raised by his foster mother Barberin, without ever knowing that he is actually an orphan, wanders to various places with an old travelling performer, overcomes a variety of hardships after the death of the old man, and is reunited with real mother while, along with Rémi's growth, depicts the various regions of France where he wandered. In this translation, the names of the characters are changed to Japanese-style names, with the main character Rémi as "Tami" and Barberin as "Nao".

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, NAITŌ Arō (Tr.), Hoshi no ōjisama, Iwanami shoten, 1953 [児953.8-Sa22]

This is the first translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's (1900-1944) Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince) (1943). Saint-Exupéry worked as a pilot in civil aviation and for the postal service, and also wrote a series of works which were well received based on his own occasionally dangerous experiences. During World War II, in July 1944, he departed for southern France on a mission as a member of the Allied Forces aerial reconnaissance party and disappeared.

This work, which tells the tale of the friendship between the narrator, a pilot who made an emergency landing in the Sahara Desert, and the Little Prince who came from an asteroid, is written in a poetic style interlaced with allegory, and became a best seller after the author's death when an English edition and French edition were published in New York in 1943. The work has been translated into the languages of over 130 countries and regions. In Japan, the translation by French literature scholar NAITO Aro (1883-1977) was published in 1953, and is still loved even today under the Japanese title Hoshi no ōjisama (lit. Prince of the Star). The many simple illustrations inserted were also drawn by the author himself.

Translation of French poetry

UEDA Bin (Tr.), Kaichōon, Hongōshoin, 1905 [98-192]

This is a collection of translations by English literature scholar and poet UEDA Bin (1874-1916). The collection contains 57 works of 29 European poets, mostly focusing on modern times, of which 14 are French poets. In addition to injecting a new trend by adding new poetic forms and meters into the existing style of new-style poetry, the work also introduced French symbolism poetry to Japan for the first time, having a major impact on poetry circles. From this work onwards, a succession of translated poetry collections, from NAGAI Kafu's Sangoshū (lit. Coral Anthology) [338-148] published in 1913, to HORIGUCHI Daigaku's (1892-1981) Gekka no ichigun (lit. Gathering in moonlight) [531-30] played a decisive role in the formation of modern poetry in Japan. Rakuyō, the translation of Paul-Marie Verlaine's (1844-1896) Chanson d'automne, which begins with, "Les sanglots longs, Des violons, De l'automne, Blessent mon Coeur, D'une langueur, Monotone. "("Leaf-strewing gales, Utter low wails, Like violins, — Till on my soul, Their creeping dole, Stealthily wins....") is particularly famous as an excellent translation.