- Top

- > Calendar History

- > Calendar History 2

Calendar History 2

Later calendar amendments

As the Edo period wore on and knowledge of astronomy grew more sophisticated, the discrepancy between the calendar and actual astronomical events, such as eclipses of the sun and moon, became an issue, there arose a movement within the shogunate to amend the calendar. Prior to then, the calendar was made each year based on the Senmyo-reki brought from China in the 4th year of Jogan (862), but as the same method had been used for more than eight centuries, it was deemed consistent with the situation prevailing at the time.

In the 2nd year of Jokyo (1685), a method of making the calendar was devised by Shibukawa Harumi, marking the first attempt by a Japanese, with the amended version known as the Jokyo calendar. Later in the Edo period, the calendar was revised several times, the results respectively called the Horeki (1755), Kansei (1798) and Tenpo (1844) calendars. Through these amendments, a more accurate lunisolar calendar was devised incorporating Occidental astronomy. Calendar calculation was made by the "Tenmongata" (officer in charge of astronomy) in the Edo shogunate, with notes added by the Kotokui family, descendants of the Kamo family, after which calendars were issued by publishers in various regions.

| Title | Creator | Physical data |

|---|---|---|

| Fugaku hyakkei. [pt.] 3 | Katsushika Hokusai | 1v. ; 23cm x 16cm |

| Date | Publisher | Place |

| 1834-1835 | - | - |

| Note | Subject(NDC) | Call No. |

| One of 3 vols. | 721.8 | 166-62 |

This is a view of the Asakusa Astronomical Observatory in "Torigoe-no-fuji," compiled in "Fugaku-hyakkei," a collection of woodblock prints by the noted Ukiyoe artist Katsushika Hokusai, which was used by the Tenmongata of the Edo shogunate for astronomical observation. The globe in the center is a "Kontengi"(astrolabe), an instrument used to study movements of the heavenly bodies. The Asakusa Observatory was built in 1782 and moved to Kudan-sakashita in the 3rd year of Tenpo (1842).

Daily life and the calendar

Calendars at first were exclusively for the use of the imperial court and noblemen, but after the dawn of printed calendars, more and more people came to use them. Farmers and merchants found them essential to know the seasons and events. In particular, when using lunisolar calendars in which the order of long and short months changed year after year, learning them proved indispensable for merchants who made collections or payments at the end of each month.

Because of this, various types of calendars were devised and used.

Local calendars

Calendars were published mainly in Kyoto, but as the demand rose, they began to sell in various regions. A very old one, the Mishima-reki calendar, published in a district corresponding to the present-day Mishima city in Shizuoka prefecture, is said to date back to the 14th century. Another is the Ise-reki calendar, which was published in what is now Ise city in Mie prefecture and widely spread as Oshi, Shinto priests of the Ise shrines, traveled through the country.

| Title | Creator | Physical data |

|---|---|---|

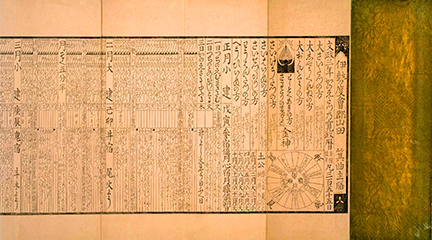

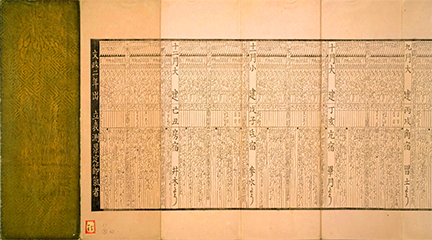

| 3rd year of Bunsei (1820) Ise-goyomi | - | 1 folded sheet ; 31 x 160cm |

| Date | Publisher | Place |

| 1821 | Mimagari Shuzen | Yamada (Ise) |

| Note | Subject(NDC) | Call No. |

| Special Ed.In the Shinjo Collection. | 449.81 | 寄別12-6-11(7-43) |

This shows an Ise calendar, the most widely diffused regional type. All were of the orihon sort (a book of a long sheets of paper folded like an accordion into pages), varying widely in size and the way of binding. This example is especially gorgeous and bound with a gold-ornamented cover.

E-goyomi (Picture calendar)

In former times when, unlike today, a great many people were illiterate, some calendars were made only with pictures. The Tayama calendar and Morioka e-goyomi, both produced in what is now Iwate prefecture, are such examples.

| Title | Creator | Physical data |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd year of Kyowa (1802) Tayama-reki | - | 1 sheet ; 24.5 x 101cm |

| Date | Publisher | Place |

| 1801 | - | Asiro-machi (Iwate-ken) |

| Note | Subject(NDC) | Call No. |

| Formerly owned by Ojima Sekiyu. | 449.81 | 本別15-21 |

Referring to the Ise calendar, this calendar was made by picturing the daily needs of life in a mountain village and stamping a wooden type on each of them. The first page featured the image of a dog, which meant it was the year of dog. Main notes were also shown by pictures. Very few remain today.

Daisho-reki Calendars

These calendars were produced to help people learn the order of long and short months. In calendars of this type, long and short months were incorporated in drawings and sentences, for which their manufacturers vied in novelty and of humor. They were widespread among the populace during the Edo period.

In "Unriddling the Daisho-reki Calendar", various Daisho-reki Calendars will be introduced.

| Title | Creator | Physical data |

|---|---|---|

| 4th year of Keio (first year of Meiji, 1868) Daisho-reki | Kawanabe Kyosai | 1 sheet ; 19 x 26cm |

| Date | Publisher | Place |

| 1867 | - | - |

| Note | Subject(NDC) | Call No. |

| Pasted in "Egoyomi harikomi-cho" | 449.81/721.8 | 寄別13-64 |

In 1868 the Edo shogunate fell and the reins of government were returned to young Emperor Meiji, ushering in an age of modernization for Japan. Reflecting the confusion associated with such a transition, riots, during which people danced while chanting "Eejanaika! (So what?)," occurred in many parts of the country. This is an example of work by Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-89), who incorporated "Eejanaika!" dancing in a Daisho-reki calendar. In the dancing circle, men represent long months, women, the short months. The men and women wear costumes connected with the monthly events or the seasons, and hold symbolic objects.

Various forms of calendars

Simplified calendars, consisting of only the well-used parts, are called Ryaku-reki (Abridged calendars). Folding them into small sections or tacking them to a post, people in the Edo period used them for daily reference. Many examples of these calendars remain today. As in the case of contemporary calendars, merchants distributed them among their customers at the year-end as a form of advertising.

| Title | Creator | Physical data |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd year of Keio (1866) Hashira-goyomi | - | 1 sheet |

| Date | Publisher | Place |

| 1865 | Ringataya Kobee | Edo (Tokyo) |

| Note | Subject(NDC) | Call No. |

| In the Shinjo Collection. | 449.81 | 寄別12-6-25 |

Abridged tatenaga (longer than wide) calendars were called "Hashira-reki", single sheet block prints tacked to a post or wall.

| Title | Creator | Physical data |

|---|---|---|

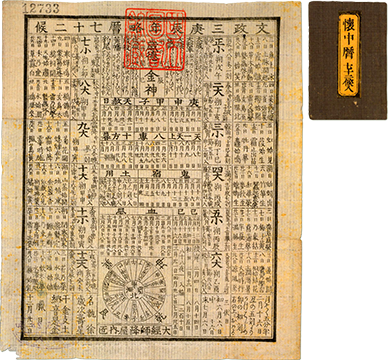

| 3rd year of Bunsei (1820) Kaichu-reki | - | 1 sheet |

| Date | Publisher | Place |

| 1820 | Daikyouji Huriya Takumi | - |

| Note | Subject(NDC) | Call No. |

| Formerly owned by Ojima Sekiyu. | 449.81 | 本別15-21 |

Kaichu-reki had a cover so that it could be folded up and carried easily.

Meiji era change

The Meiji government, established in 1868 after a lengthy revolution, undertook to modernize the nation by introducing Western ways. This included replacing the old lunar calendar with the Gregorian version in November 1872 (5th year of Meiji), which took effect the following year and continues in use today.

Since there was little time for preparation and December 3 of the 5th year of Meiji became January 1 of 6th year, a great amount of confusion prevailed. Nevertheless, scholars like Fukuzawa Yukichi supported the more logical Gregorian calendar and published books intended to diffuse it.

While the calendar Japan uses today is the Gregorian type, it still includes words to express seasons, as found in the ancient lunisolar calendar. While the calendar is renewed every year, the history and culture of Japan are engraved in it.

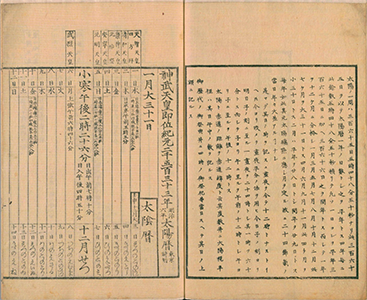

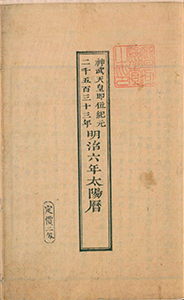

| Title | Creator | Physical data |

|---|---|---|

| 6th year of Meiji (1873) Taiyo-reki | - | 1v. |

| Date | Publisher | Place |

| 1872 | - | - |

| Note | Subject(NDC) | Call No. |

| In the Shinjo Collection. | 449.81 | 寄別12-6-28 |

The first solar calendar after adopting the Gregorian model. The principle of the calendar and an explanation of how time is determined are introduced in the preface. Because of the sudden switch, it had not spread throughout the country by the end of 1872 (5th year of Meiji). Koki, or the year of imperial reigns counting from the enthronement of Emperor Jinmu (e.g., the 6th year of Meiji corresponds to Koki 2533) was inserted, with festivals and the like feting successive emperors are mentioned in the upper column.

![Fugaku hyakkei. [pt.] 3](img/img_02_01.png)

![Fugaku hyakkei. [pt.] 3](img/img_02_02.png)