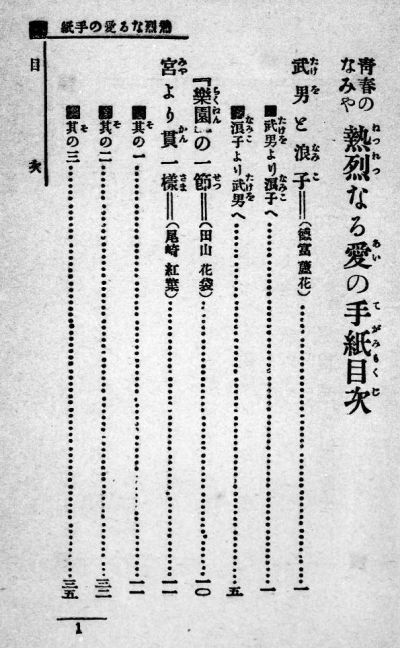

- Kaleidoscope of Books

- Expressing romance in words: the world of love letters

- Chapter 2: Love letters in the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Love letters in the Edo period

- Chapter 2: Love letters in the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods

- References

- Japanese

Chapter 2: Love letters in the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods

Even after the end of the Edo period (1603-1868), when society underwent major changes, love letters continued to be an important means of communicating people's feelings of love.

In Chapter 2, we will introduce the state of affairs in love letters since the Meiji period from three perspectives: changes in the writing style of love letters, the culture in which love letter writing flourished, and the masters of love letters.

Love letter manuals in the Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods—Unchanged feelings of love, changing words of love

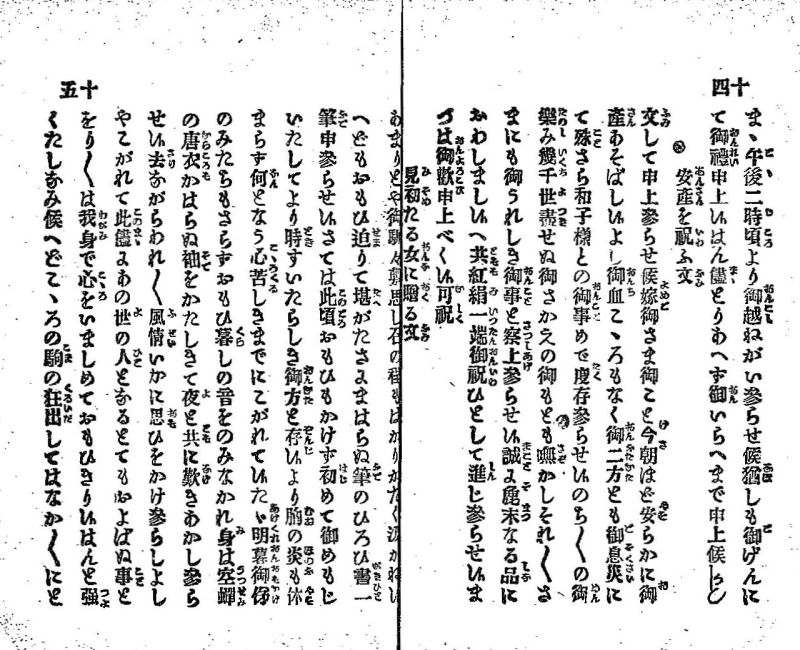

Although called “love letters,” romantic correspondence during the Edo period followed the stiffly formal conventions of the Japanese literary style call sorobun. A distinguishing characteristic of this style was to end sentences using the phrase “soro” in place of the colloquial “masu.” By the end of the Meiji period, however, the influence of a movement to unify written Japanese with the spoken language had spread, and many people were writing personal correspondence in the vernacular. Naturally, the style of love letters changed accordingly.

“I am so deeply in love with you that I writhe in torment.”

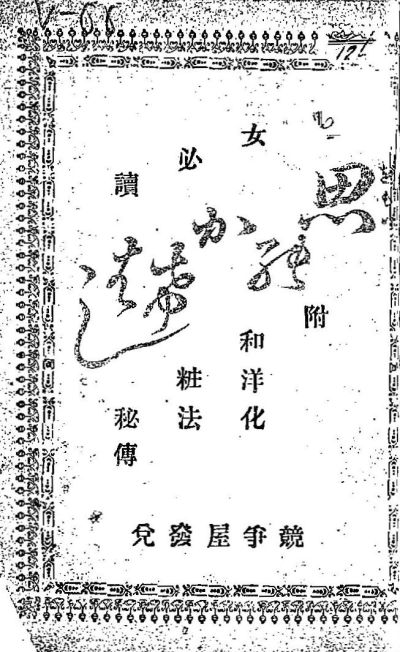

This book was published in 1889 and contains typical examples of correspondence between men and women. One of the examples, entitled “Letter to a beloved woman,” shows the writer's seriousness through use of the formal sorobun style of writing.

Since realizing I am enamored of you, the fire of passion has been burning in my heart. I am so deeply in love with you that I writhe in torment.

The latter half of this book includes instructions to women on how to apply makeup, with headings such as “How to make big eyes look smaller.”

“I've fallen for you, haven't I?”

From a young girl with bright eyes

It was nice to see you the other day. I keep seeing your face…tee-hee! I've fallen for you, haven't I? Oh my darling, if I lose my heart to you, what are you going to do? Will you grant my wish? Hmm?

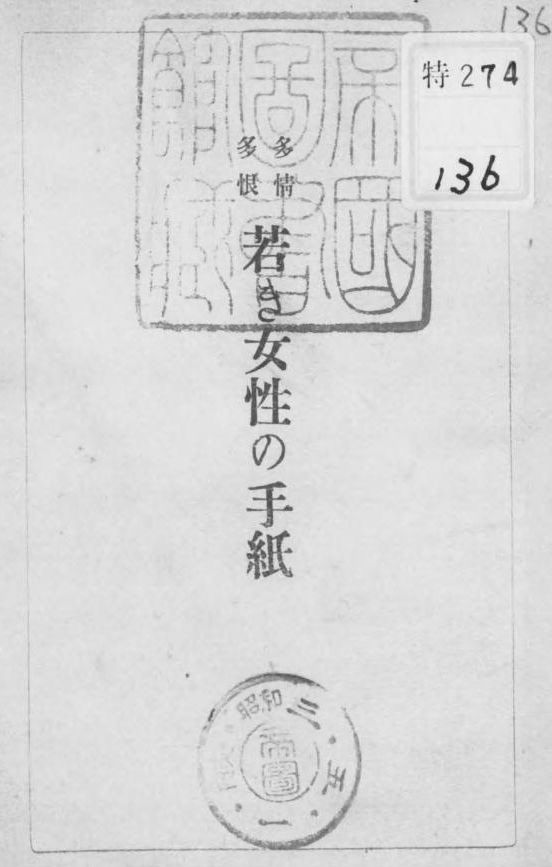

This book is an anthology letters written by young men and women during the Taisho period, although it is not entirely clear whether these letters were actually sent or not. This letter, entitled “From a young girl with bright eyes,” airily conveys the writer's feelings in a plain colloquial style.

This transition from sorobun to a colloquial style certainly made love letters more expressive.

“My face has turned scarlet.”

You don't know how happy I was to receive this surprising letter. Sometimes I wonder if it is just a dream. (…) I am so abashed and delighted that my heart is pounding, and my face has turned scarlet.

This anthology of personal correspondence was published in 1928. In the following example, a woman openly expresses her joy and shyness while accepting a marriage proposal.

Reading these letters, it is easy to imagine that people in those days were not afraid to convey their feelings in letters.

Intimate correspondence between girls—the S word

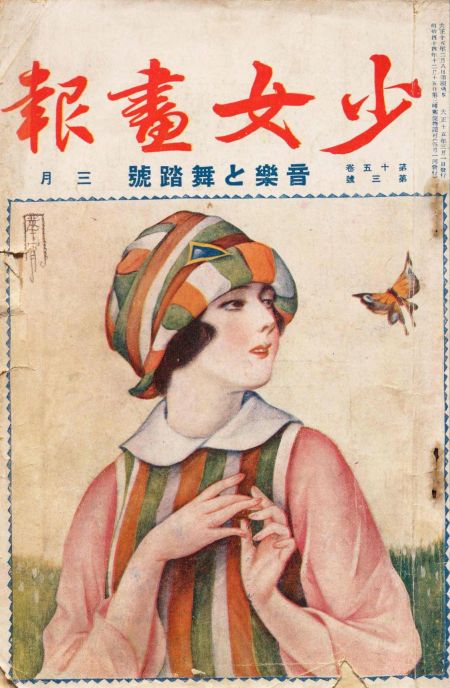

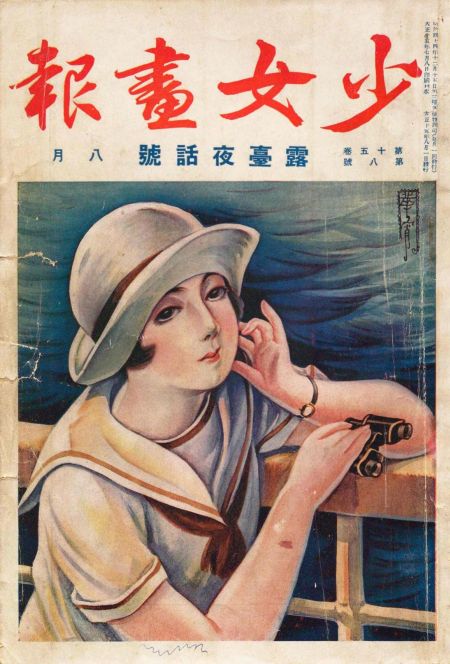

The expression of intimate feelings in letters was not limited to between men and women. From the end of the Meiji period to the beginning of the Showa period, many girls formed close friendships that were referred to at the time as “S” relationships. Girls in these relationships would sometimes write to girls magazines about their relationships.

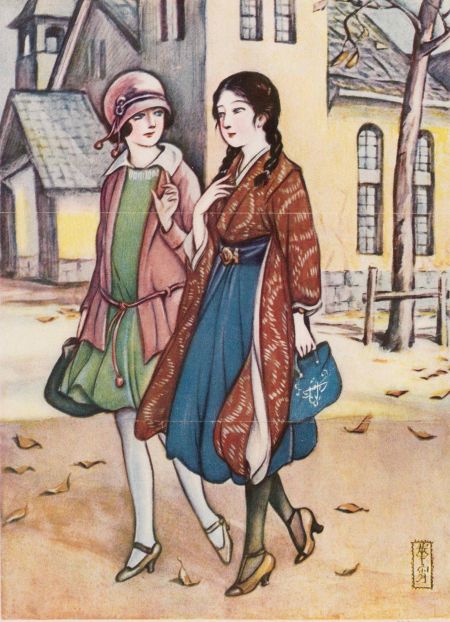

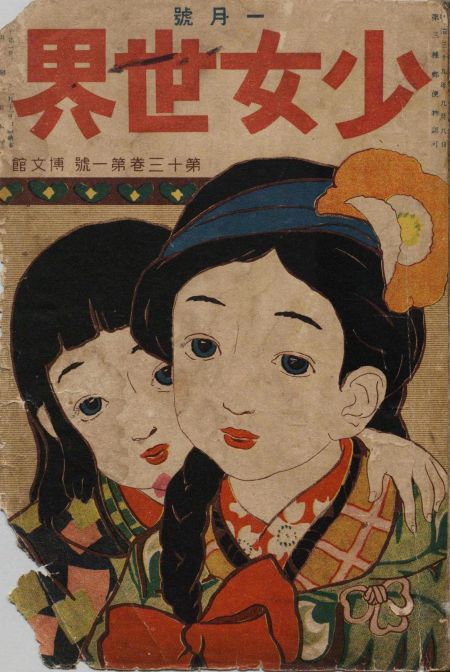

The following picture of two girls enjoying a walk together is by TAKABATAKE Kasho, who drew numerous illustrations for girl magazines.

The S word in girls magazines

This colorful cover to the magazine Shojo sekai (Girl's World) is a typical of the girls magazines that were popular during the early 20th century.

The S word was “sister” and was used in reference to and intimate friendship between two girls that was neither just a casual friendship nor a truly romantic relationship. But fictional accounts of girls in S relationships were popular in these magazines, and there were girls who for whom such relationships were a part of their school life. One significant part of an S relationship was the exchange of intimate correspondence. What kind of letters did they send to each other?

Ardent letters from girl to girl

You know nothing of the things I hold for you. My sighs, my monologues, my tears, my letters. But each and every one of them is here waiting for you. (…) My beloved O, why are your eyes so beautiful? Why do your eyes hold my heart captive? O, my heart hurts to bursting. What on earth should I do about these feelings?

A letter entitled “Things I wanted to tell you,” contributed by a reader.

This letter was contributed to a readers' column called Letters of the Roses in the girls magazine Shojo gaho. A large number of letters written by girls to a specific partner were published in this column. Many were as passionate as this one, and could only be considered love letters from one girl to another.

No one knows if these girls were actually sending each other letters this passionate. But reading the letters that appeared in these magazines gives us and idea of the special feelings of closeness these girls held for each other.

A love letter from someone bewildered by confession

Dear Yumika

An ephemeral dream that sprang up suddenly in your pure maiden heart. Longing… to betray and hurt that incomparably beautiful longing is more painful to me than dying. But to accept your desire willingly in silence is more anguish than that. What should I do? (…) Hayama-san! She says that she dedicates a fleeting pink dream to you.” When they pointed at you, I was flustered. —I wondered what it would be like if I had such a cute little sister,—Your pitch-black halo braid updo hairstyle and your innocent face like a white doll. I was horrified...you were a princess in a faint midday dream.

A letter entitled For a holy girl, contributed by Hayama Mikiyo

This is also a letter from Letters of the Roses in Shojo Gaho. Hayama Mikiyo, the writer of the letter, who was favored by a junior girl named Yumika, expressed her uneasy thoughts that she could not live up to those feelings.

From the lines of the cronies teasing the author and the description of Yumika's appearance, the scene of the two of them glaring at each other in the school comes to our mind beyond time. By the way, Yumika’s hairstyle, a halo braid updo hairstyle, was popular at that time in Japan.

Higuchi Ichiyo—a writer of brilliant love letters

HIGUCHI Ichiyo was a writer who lived during the Meiji period and left behind a number of brilliant love letters. She wrote a number of works of literature over the course of her brief life and is now familiar as the portrait on the 5,000-yen bill in Japan. There are a number of interesting stories about her love letters.

Born in Tokyo in 1872, Higuchi Ichisyo entered the Haginoya poetry academy of Utako Nakajima as a teenager and began writing stories in 1891, after becoming a student of NAKARAI Tosui. Not long thereafter, she died of tuberculosis in 1896.

For more information about Ichiyo, please do check out our digital exhibition Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures.

Ichiyo's style guide for letter writing

Ichiyo authored a style guide for writing letters in the sorobun style. In here style guide is an example of a letter that is addressed to a former high school classmate and expresses the writer's sorrow at having lost touch as well as a yearning to regain lost intimacy. Although the style guide contains no examples of love letters per se, this particular example has the ambience of a love letter, and some people have noted the similarity of the emotions expressed here to those in S relationships mentioned earlier. The opening sentence of this letter—“The other day, I caught a vague glimpse of you in the park in Ueno…”—is a beautifully literate example of Higuchi's talent.

Ichiyo's romance

When Ichiyo was 19 years old, she met and became infatuated with her writing instructor, Nakarai Tosui, who was 12 years her senior, and a number of her letters to him remain extant. About a year after they met, as rumors that they were romantically involved began to spread, she wrote a letter telling him that she could no longer continue their relationship. The letter is included in Higuchi ichiyo zenshu vol.4(3) (published by Chikumashobo,1994. [KH134-2]).

Addressed to Nakarai Tosui, on July 8, 1892

I have only ever thought of you as an older brother, to whom I could always turn for counsel. And yet because of these rumors, everyone, my family included, misinterprets our relationship. I can't tell you how disappointed I am with this situation.

Addressed to Nakarai Tosui, on August 10, 1892

You are to me a brother and a mentor. No matter what they say about you, I know in my heart it cannot be true…

Although she never directly discusses her feelings for Tosui, her description of how she respects him followed by her expression of chagrin at no longer being able to meet with him freely because of the rumors clearly conveys how she is trying to disguise the true depth of her feeling for him.

Loves arranged by Ichiyo

Ryuusenji-cho, Shimoya Ward, Tokyo, where Ichiyo ran a small shop for a living, and Maruyama-Fukuyama-cho, Hongo Ward (present-day Nishikata, Bunkyo Ward, Tokyo), where she later moved, were both close to a red-light district and a saloon district, and she saw and heard the way the people who worked there lived.

In her diary, dated January 4, 1895, she wrote that she had written love letters on behalf of the women who worked at the saloon next door while she was living in Maruyama Fukuyama-cho, Hongo Ward. She wrote, “Women come and ask me to write letters on their behalf, but the addresses are always different and the number of letters is large,” and “Do these women sometimes have true love?”

From these descriptions, we can see their uninhibited yet ephemeral love situation.

These interactions with people from various perspectives were utilized in novels such as Takekurabe and Nigorie.

Column: Love letters in literature

This book is a collection of love letters from famous literary works and from the writers themselves.

You can enjoy love letters of various kinds. The letters of Takeo and Namiko in TOKUTOMI Roka's Hototogisu (Namiko), Omiya's letter to Kan'ichi in OZAKI Koyo's Konjiki yasha (The Golden Demon), and Anunciata's farewell letter to Antonio in Andersen's The Improvisatore, translated by MORI Ogai.

There are also other similar books that seem to have been based on this, such as Kindai meisaku ni arawaretaru ai no shokanshu (Letters of Love in Modern Masterpieces, [特108-79]) and Ai no shokanbun (Letters of Love, [特113-632]).

Next

References