- Kaleidoscope of Books

- Infectious Diseases in Books

- Malaria, Influenza

- Introduction

- Smallpox, Plague/Black Death

- Cholera, Tuberculosis

- Malaria, Influenza

- References

- Japanese

Malaria

Malaria is caused by several species of Plasmodium, transmitted by mosquitoes and passed from one person to another. One of the distinctive symptoms is periodic fevers.

Malaria in Japanese classics

A disease called okori, which is considered to be malaria, often appears in Japanese classical literatures.

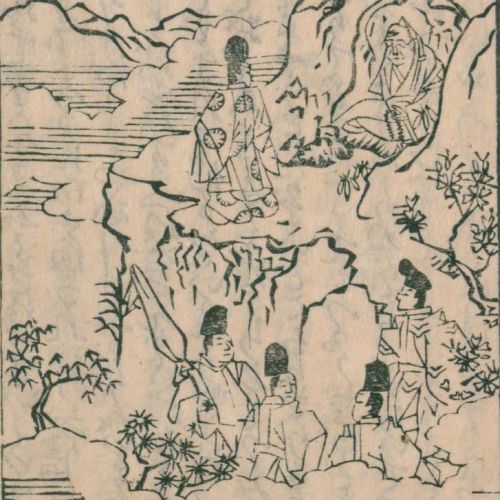

Kitayama no hijiri no moto he iku Hikaru Genji (Hikaru Genji visiting a saint in Kitayama)

Hikaru Genji visits a saint in Kitayama to pray for his recovery from okori at the beginning of Genji monogatari chapter 5, Wakamurasaki.

TAIRA no kiyomori hi no yamai no zu (Taira no Kiyomori suffering a high fever)

Taira no Kiyomori suffered from a high fever in his end. Heike monogatari (The Tale of the Heike) describes that his body became extremely hot, as if building a fire. Although the name of the disease is not stated, Kiyomori must have been infected with okori.

World War II and malaria

In Japan, malaria epidemics sometimes occurred from the Meiji period to the early Showa period but by 1935, it settled down except in some areas. However, soldiers demobilized from Southeast Asia after World War II again brought the threat of malaria.

OOKA Shohei, Furyoki (Taken Captive: A Japanese POW's Story), Sogensha, 1949. [a913-1237]

Main character of this novel is a soldier who served in World War II, based on the author's own experience. Malaria strikes a unit which has moved to Mindoro Island in the Philippines. The protagonist also gets infected with malaria, leaves their corps and encounters a U.S. soldier over the grass.

ODA Toshio, Saihatsu marariya no yogo oyobi chiryo (Convalescence and treatment of recurrent malaria), Nihon isho shuppan, 1947. [493.88-O219s]

After World War II, many repatriated citizens infected with malaria came back to Japan. This material shows how to deal with the malaria they suffered from. Such a book might have been in great demand when published in 1947.

Sengo mararia no ryukogakuteki kenkyu (Epidemiologic research of malaria after World War II)

This is a review of the epidemic situation of malaria due to repatriates by 1952. As a result, it describes “Imported malaria by enormous returnees was so concerned during the war, but it has been disappeared within five years since the end of the war.” Malaria brought by repatriates seems to have come to an end at an early stage.

Influenza

1918 flu pandemic―Spanish flu

In Japan, the first large influenza epidemic broke out in 1890, followed by the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, the Asian flu pandemic of 1957 and the Hong Kong flu pandemic of 1969. The 1890 epidemic killed well-known figures such as MOTODA Nagazane (Emperor Meiji’s close aide) and SANJO Sanetomi (Grand Minister of State). However, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 caused the most serious damage.

Motoda Nagazane / Sanjo Sanetomi

HAYAMI Akira, Ed., Tokyo Seiryo Inryosui Dogyo Kumiai, Nihon o osotta supein infuruenza

(The Spanish

influenza which struck Japan), 1935. [特220-525]

Hayami Akira (1929-2019), a historical demographer, collected actual epidemic conditions based on local newspapers and statistical data from the time of the epidemics. The content includes the occurrence of this influenza in foreign countries, as well as the first wave (from autumn in 1918 to spring in 1919) and second wave (from autumn in 1919 to spring in 1920) in Japan, which are sorted by region in this book. It also introduces several incidents like the spread in the Japanese protected cruiser Yahagi and the impact on the sumo wrestling community and other businesses, providing a glimpse of the true state of the Spanish influenza.

Jiji Manga (Editorial cartoon)

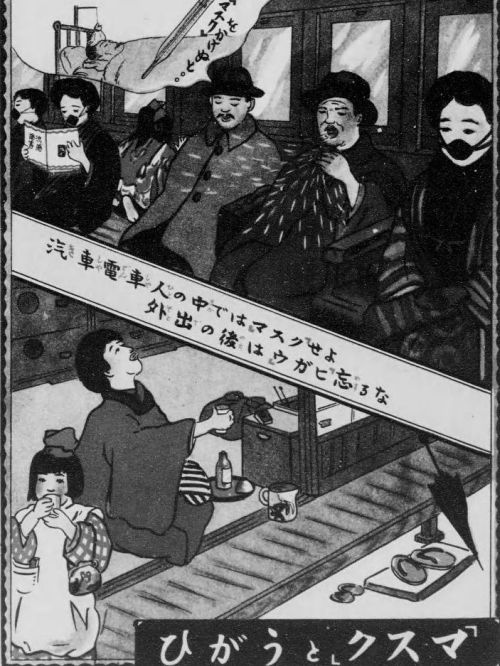

This caricature depicts a doctor in the midst of an epidemic. A doctor who is very busy with taking care of patients goes to the theater, hiding his face with a mask. In the last frame, he mutters to himself, “I wonder whether a mask is effective or not, but it is very useful to conceal myself from patients.” Masks were widely known for infection prevention, although their effectiveness was considered uncertain at that time.

Influenza prevention measures

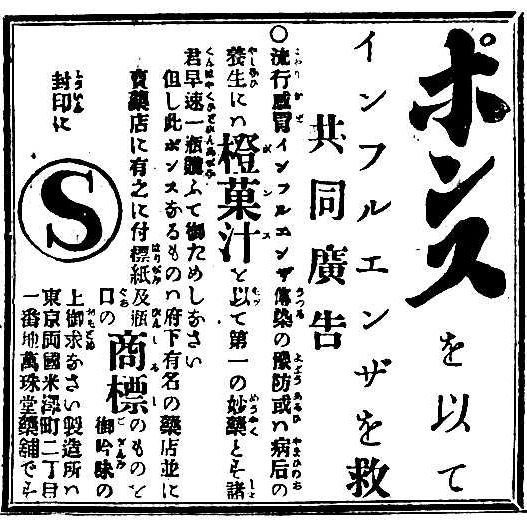

A lot of advertisements emerged pitching effects for preventative care. The following are examples of some newspaper advertisements.

Advertisement of the medicine warehouse Manjyudo

The Tokyo mohan shokohinroku* says that YOSHIDA

Yasugoro, an owner of Manjyudo, developed Ponsu,

which has a characteristic fragrance and fine taste. It also

mentions that Ponsu is very effective for all febrile

symptoms from typhus, influenza and measles. How well

did it work actually?

*Edited by NAKAYAMA Yasuta in 1907. [34-296]

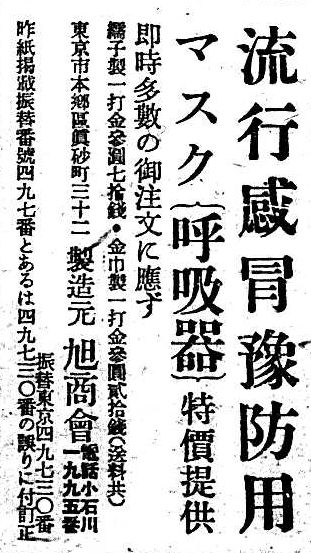

Advertisement for masks

Masks went on sale for influenza prevention. This advertisement shows the rising demand of masks at that time.

Advertisement for Rhumex

This advertisement says, “a few drops of Rhumex on your

pillow helps you have a good sleep and prevents you from

catching influenza.”

Another advertisement mentions Rhumex as a pleasant

modern inhalant. An explanatory label describes “This is

a mascot for the modern person whose fragrance

removes fatigue, refreshes one’s spirit and clears one’s

head.” The main use of Rhumex might have been

invigorating by smelling rather than preventing infection.

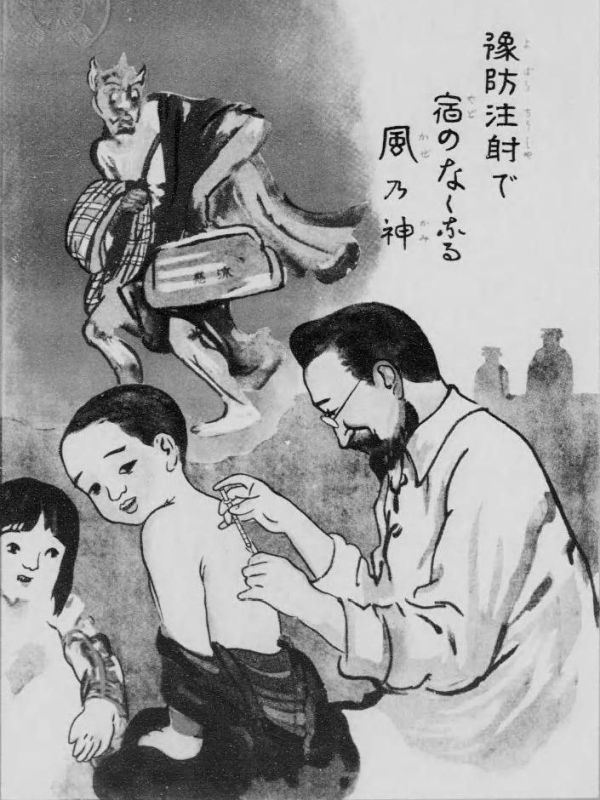

In addition to the above, the government widely promoted preventative measures. Ways of dealing with disease like masks, gargling and vaccinations, have not changed since these days when people of that time did not know what caused influenza.

This book was compiled based on the experiences of the Spanish influenza, including the statistical data of patients, pandemic situations in each country, research in symptoms and remedies.

Next

References