- Kaleidoscope of Books

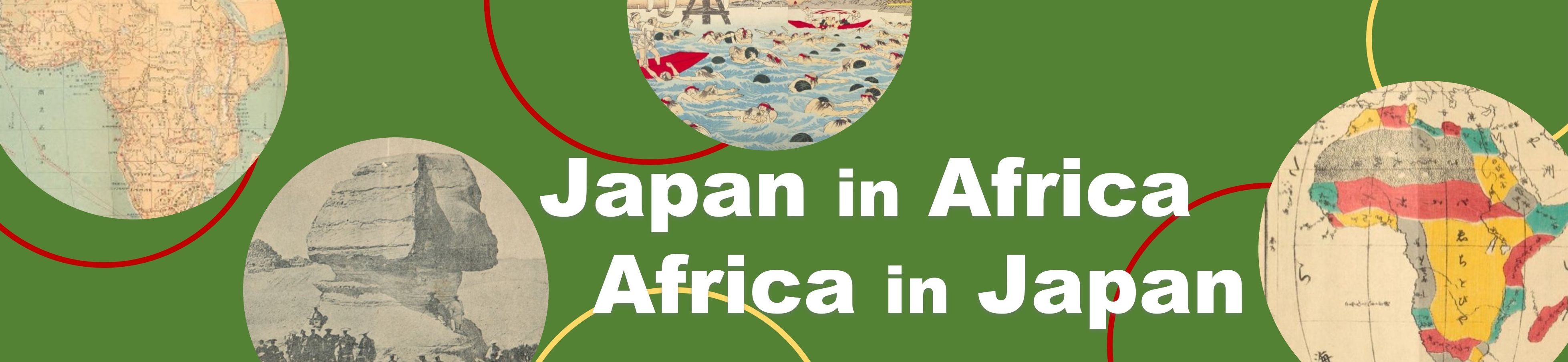

- Japan in Africa, Africa in Japan - Exchanges of Culture and People

- Chapter 2: Africans who came to Japan

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Japanese who traveled to Africa

- Chapter 2: Africans who came to Japan

- Chapter 3: Exchanges between Japan and Africa

- Chronological table

- Conclusion/References

- Japanese

Chapter 2: Africans who came to Japan

From the Sengoku period (civil war era mainly in the 16th century) to the present day, many Africans have visited Japan for various reasons. This chapter describes some of them and their relationship with Japan.

To the early modern times: footsteps of several Africans

African people coming to Japan

African people are believed to have first visited Japan during the Sengoku period as servants or slaves of European ships from Portugal and Spain.

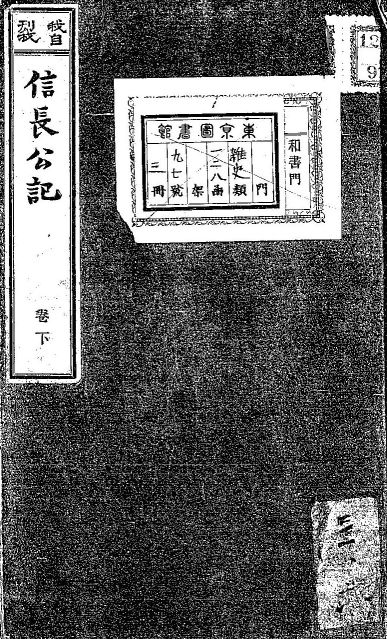

In Shinchō Kōki (信長公記, A Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga), a biography of ODA Nobunaga, there appears Kurobōzu (黒坊主, a black priest), who first attended the Jesuit priest Valignano and later served Nobunaga. He is described as follows: “This man looked robust and had a good demeanor. What is more, his formidable strength surpassed that of ten men,” which suggests that he was highly appreciated by people at that time including Nobunaga himself. While he was called Yasuke (弥助) in Japan, his real name in Africa is unknown.

The Tensho Boys' Mission mentioned at the beginning of Chapter 1 should know African people because Tensho Nenkan Ken-ō Shisetsu Kenbun Taiwaroku (天正年間遣欧使節見聞対話録: lit. The dialog of the Tensho Boy Mission to Europe) [226-29] records their statement that they had "seen many of those black men coming towards us before" they visited Africa. Furthermore, according to a report, ARIMA Harunobu, one of the daimyo (feudal lord) who sent the mission, and his army were helped by Africans and Malabarians (Indians). In Fróis’ História do Japão [GB315-21], it is written that in the battle between the Arima-Shimazu allied army and the Ryuzoji army, in the absence of Japanese gunners, a cannon was loaded “by a Kafr (=African)” and shot by “a Malabarian” and “they served more effectively than 1,000 soldiers.” There are other various records that mention people from Africa, such as TOYOTOMI Hideyoshi's reward for “Kafr” dance.

Exchanges in Dejima

In the Edo period (1603-1868), although exchange with overseas countries decreased under the national isolationist policy, African people did not disappear from Japan completely.

In Nagasaki, one of the open windows to foreign countries during this era, the records of judgments given by the magistrate's office include cases involving Africans then called Kurobō (black man). The content was such that Japanese “guided Kurobō and went to the red-light district” or “made a shōgi (Japanese chess) board for Kurobō and received fabric as a reward.” At least for some Japanese in Nagasaki, even if the shogunate forbade it, Kurobō were apparently familiar neighbors.

At that time, the term Kurobō referred to people with dark skin, including not only Africans but also people from Southeast Asia. It seems certain that African people as well as Asian people stayed in Nagasaki, judging from a description in Kōkan Saiyu Nikki (江漢西遊日記) [GC274-57] by SHIBA Kōkan (司馬江漢) that “Kurobō came from tropical regions such as Java Island or Monomotapa in the African continent.” Today “Monomotapa” is regarded to refer to a region near present-day Zimbabwe.

Independence of African Countries—Long Relationship between Ethiopia and Japan

While interactions between Japan and other countries gradually increased in the Meiji period (1868-1912), many parts of the African continent were already colonized by European countries and it was not easy for African people to visit Japan. However, Ethiopia, one of the few independent countries in Africa, sent envoys to Japan several times.

Japan introduced in Africa

In 1930, Japan and Ethiopia signed the Treaty of Amity and Commerce. In the same year, a Japanese minister attended the coronation of Haile Selassie I, the emperor of Ethiopia. The next year, in 1931, an Ethiopian envoy visited Japan to return the favor and received a warm welcome.

7)Heruy, Dai Nihon (大日本: Great Japan), translated into English by Oreste Vaccari, translated into Japanese by Enko Vaccari, Eibunpo-Tsuron Hakkojo, 1934 [669-19]

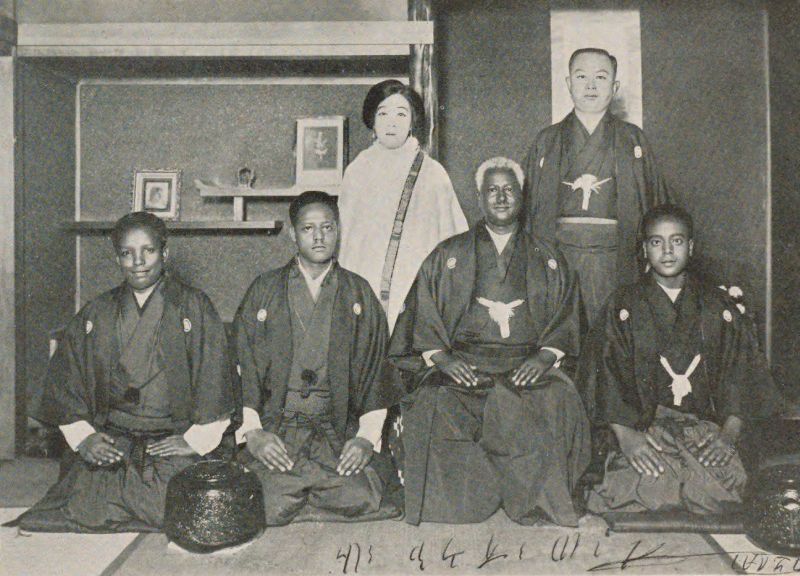

The mission to Japan in Japanese clothing.

The second from the right in the front row is Heruy and on the right end is Lij Araya Abeba

Heruy, who visited Japan as the special representative for the Ethiopian envoy, wrote a book on Japan in 1932 after returning to Ethiopia. In 1934, the Japanese translated edition of the book was published under the title Dai Nihon [669-19]. This book includes records of visits to various places and descriptions on Japanese customs as follows: “There are innumerable large and small factories such as silk reeling, paper making, machinery, manufacturing, airplane manufacturing, shipbuilding, weapons, newspapers and printing,” “Even in our country, Ethiopia, we must put a lot of effort into the industry.” They suggest his intention to follow the modernization of Japan. The book contains photographs taken in various places, from modern facilities such as factories and military ports, to unique Japanese landscapes such as shrines, temples and scenic spots.

Ethiopian royalty in love?

It is said that Lij Araya Abeba, a cousin of the Ethiopian emperor who accompanied the Heruy delegation, was impressed by the grace and beauty of Japanese women. After consulting with his Japanese counselors, he advertised in the newspaper to seek a bride. The number of applicants reached as many as 20 and KURODA Masako, a viscount’s daughter, was selected as the first candidate.

When she became the candidate, she published a booklet entitled Akeyuku Ethiopia (明け行くエチオピア: lit. The Dawning Ethiopia) [特244-432] in which she expressed her determination to marry an Ethiopian. She also noted that it was not a rash idea for her because she always had an interest in foreign countries from childhood and had continued her studies and research, and said she would marry for the sake of Japan and Japanese women. Her account that her resolve to marry did not come from vanity or a light “Arabian Night” longing might be a reaction to misunderstanding about her often seen in the media. However, due to a series of circumstances, the marriage was called off.

The first state guest from Africa since World War II

Relations with Ethiopia continued after World War II. In 1956, Haile Selassie I, the emperor of Ethiopia, visited Japan as a state guest and the first post-war banquet at the Imperial Palace was held. Newspapers at that time reported the arrival of the emperor with pictures. They say that he expressed his interest in Japan's economic development and mentioned its cultural traditions.

On the same day, there were articles which reported the visit of Japanese government officials to the Middle East and Africa, and the launch of a regular service route to West Africa by a Japanese ship company. These indicate that Japan at that time also showed an economic interest in various parts of Africa other than Ethiopia.

According to the article “Ko Haile Selassie Heika Gohounichi no omoide (故ハイレ・セラシェ陛下ご訪日の憶い出: lit. His Late Majesty Haile Selassie: Remembering Your Visit to Japan)” written by Yamazu Zen-e in the 9th issue of Nihon-Ethiopia Kyokai Kaiho (日本エチオピア協会会報: lit. Bulletin of Japan-Ethiopian Association) [Z8-971], the emperor visited temples, shrines and factories in Tokyo, Nikko, Nagoya, Kyoto, Nara and Osaka for 12 days and was interested in many things in Japan. He finally “invited an advisory group for the emperor” and “employed three Japanese women as court ladies” in order to ask for the cooperation of Japanese people for the development of Ethiopia. The issue also includes articles written by former members of the advisory group and the former chief court lady. Each article describes their three years of experience working in Ethiopia.

From the Year of Africa—From New Countries

The year 1960 is called “the Year of Africa,” because many African countries achieved their independence around this year. They opened embassies and sent diplomats to Japan, and the number of Africans visiting Japan increased.

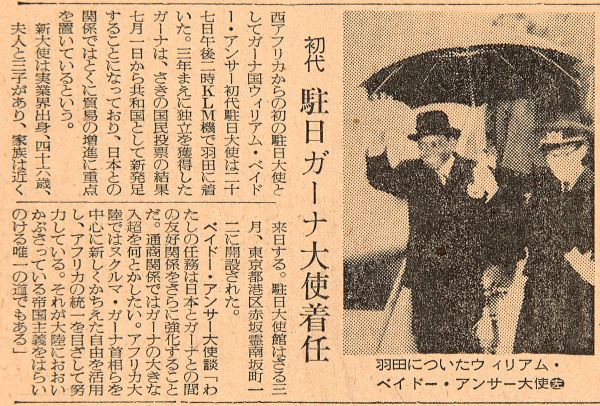

Diplomats from new countries

According to Reading history of diplomacy from embassy distribution (大使館国際関係史) [A72-J2] written by KINOSHITA Ikuo, embassies of African nations were opened one after another around “the Year of Africa" in Japan. For instance, the Ethiopian embassy was opened in 1957 and the Nigerian embassy in 1964. The first West African embassy opened in Japan was Ghana in 1960, which became independent in 1957. Its ambassador stated that he would further strengthen the friendly relations between Japan and Ghana.

As we saw in Chapter 1, the death of NOGUCHI Hideyo in Ghana led to the establishment of the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research at the University of Ghana. On top of that, most cocoa beans imported into Japan are produced in Ghana. The website of the embassy of Ghana![]() says friendly relations between Japan and Ghana have been maintained for many years. We can say that the wish of the first ambassador has been fulfilled.

says friendly relations between Japan and Ghana have been maintained for many years. We can say that the wish of the first ambassador has been fulfilled.

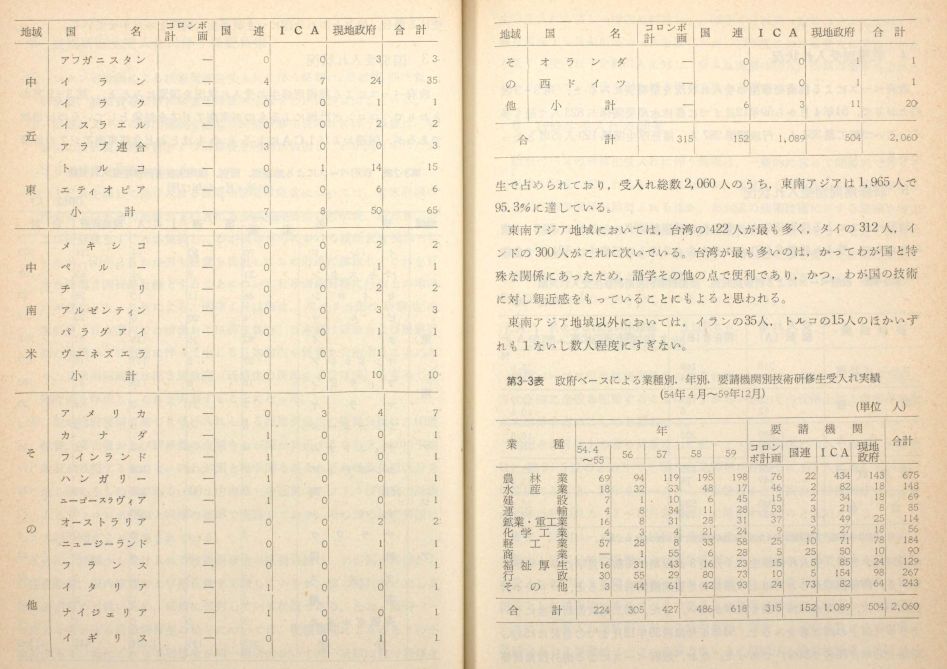

Learning in Japan

Some people from African countries visited Japan to trade, negotiate for development aid, or study. Keizai Kyoryoku no Genjou to Mondaiten (経済協力の現状と問題点: lit. The Present Situation and Problems of Economic Cooperation) [333.8-Tu783k] edited by the Trade Promotion Bureau of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, records visits to Japan from various African countries. It states that "Japan received a request from the Nigerian government mission for aid for its economic development in July 1961." According to the book, Japan accepted trainees from the United Arab Republic, Ethiopia, and Nigeria. Though the number of trainees was only 1 in 1960, it increased every year. In 1962, for example, the Japanese government accepted as many as 40 trainees from Nigeria.

The success of African Athletes in the Tokyo Olympics

Athletes from 22 African countries participated in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the first Olympic Games held in Asia. The number of participants varied from 77 athletes from the United Arab Republic (Egypt) to 1 athlete from Cameroon and Niger. In a photo book '64 Tokyo Olympics [780.6-A839s], African athletes are featured in photos such as "Ethiopian flag-bearer and marathon runner Bikila Abebe," "Ghanaian players in Kente, national clothes of Ghana," and "Chadian athlete who brings desert atmosphere into the stadium." Abebe won two consecutive Olympic titles for the first time in the history of the marathon, and some athletes won medals in athletics and boxing. Their records and photos are on the Olympic Movement website![]() .

.

Dai 18 Kai Olympic Kyogi Taikai Tokyo-to Hokokusho (第18回オリンピック競技大会東京都報告書: lit. Reports of Tokyo Metropolitan Government on the 18th Olympic Games) [780.6-To458d] states that “on this day, the players of the Republic of Zambia, which had emerged from Northern Rhodesia as the 36th independent country in Africa, were waving the new national flag high” at the closing ceremony. As symbolized by this, the image of African people must have impressed the Japanese people in this Olympics, in which newly independent nations participated.

Apartheid and Literary Men

Before World War II, African folktales and legends were introduced to Japan through books such as Africa Shinwa Densetsu-shu (阿弗利加神話伝説集: lit. African myths and legends) [388-Si511]. As writers of modern literature based on tradition were born in various places, their works were also translated into Japanese.

The NDL owns works by artists from African countries, such as Mazisi Kunene, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, and Sembène, as well as works by Nobel Prize-winning authors such as Soyinka and Coetzee. The works of African writers cover a variety of themes, including the confrontation with colonialism, the relationship between ethnicity and nation, and the perspective of gender.

The South African poet Mazisi Kunene visited Japan several times and had a great influence on the young generation. Under this influence, the term “Kunene Shock” was born. His first visit to Japan in 1970 is recorded in the magazine Shin Nihon Bungaku (新日本文学: lit. New Japanese Literature) Vol. 25, No. 6 [Z13-572], and in the book Asia Africa no Bungaku to Kokoro (アジア・アフリカの文学と心: lit. Asian and African literature and minds) [KE162-27], which includes the articles published in the magazine. The title is shocking: “The South African Poet Mazisi Kunene Visits Japan: Japan Is Killing Us.” It shows the fact that “the Japanese government supported the white republic founded on complete racial discrimination for the sake of trade” is at the expense of black people’s blood.

As explained in Chapter 1, “Foreign Minister Kimura's Visit to Africa,” Japan, which had never colonized the African continent, was sometimes criticized by Africans for its relations with apartheid and other issues. It is sometimes necessary to remember even now that the phrase "Japanese prosperity depends upon our blood" is used in this document.

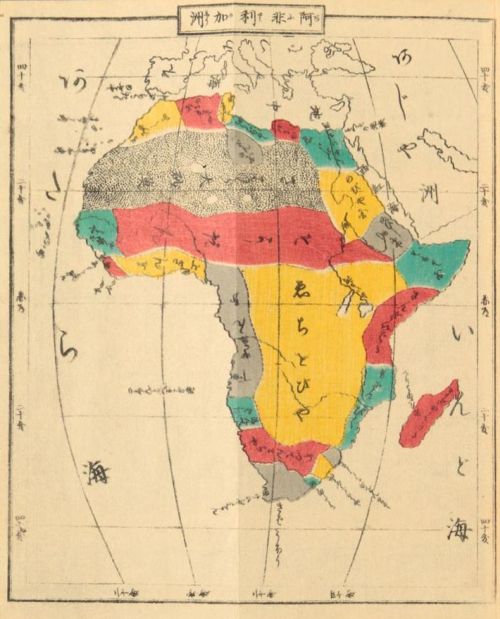

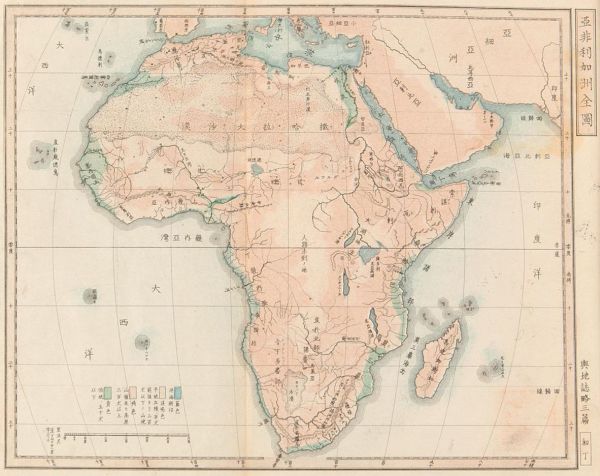

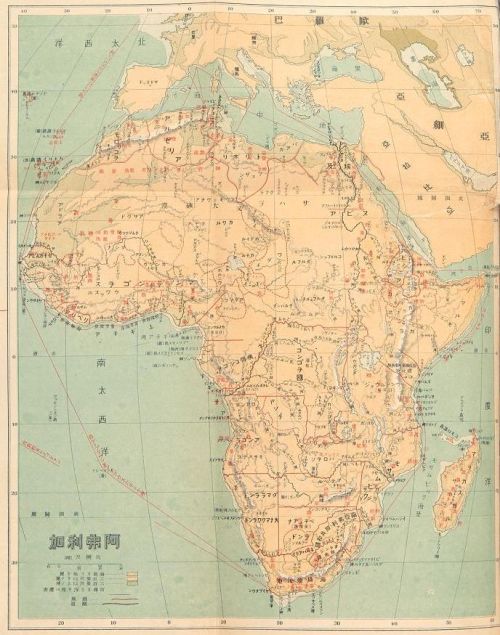

Column: History of maps of Africa

Establishment of the African map

During the Edo Period (1603-1868), maps showing the African continent such as Konyo Bankoku Zenzu (坤輿万国全図: A map of myriad countries of the World) also existed in Japan, but it was after the Meiji Period (1868-1912) that the Japanese became widely aware of African geography. Since the Meiji Restoration (1868), the geography of countries around the world was introduced to Japan, and many foreign geography books were published. Among them, FUKUZAWA Yukichi's Sekai Kunizukushi (世界国尽: All the countries of the world, for children written in verse)1869 [特54-102] and UCHIDA Masao's Yochishiryaku (輿地誌略: A Compilation of Geographical Knowledge) 1929-38 [6-231] became bestsellers and were read by people of all ages.

According to the map of Africa recorded in “Volume 2: Africa” of Sekai Kunizukusi, although the names of coastal countries and place names are fairly accurate, most of the continent consists of 3 parts: “Sahara Desert," "Sudan," and "Ethiopia". The latter 2 are not "Sudan" or "Ethiopia" as countries. They are thought to be the names of regions. In any case, it seems certain that there was a lack of information on inland Africa.

The map included in "Volume 8: Africa" of Yochishiryaku was written based on a geography book which Uchida obtained when he studied in the Netherlands. Compared to Sekai Kunizukushi, it has much more complete geographical information on rivers and mountainous areas. However, there is a common lack of information on inland areas, such as the description "uncharted land" in the center of the continent.

The map published in the geography textbook Shinsen Bankoku Chiri (新撰万国地理: lit. New world geography, 1893) [43-237ロ] includes slightly inaccurate locations of national boundaries, but the amount of information on the maps dramatically increased since many European countries reported the situation of inland Africa.

Independence of African countries

After World War II, as African countries became independent one after another, Africa entered a new era. This GIF shows how countries from Libya in 1951 to South Sudan in 2011 achieved independence and repainted their maps.

Next Chapter 3:

Exchanges between Japan and Africa