Column <Tokyo>

9 Theatrical Performances and Theaters in the Meiji Era (3):

Movement for Raising the Level of Theater in Japan and Debate on the Construction of a National Theater

In 1886, after returning from Britain, Suematsu Kencho, insisting that plays performed in Japanese theaters were uncivilized and disgraceful, formed a group to heighten the standard of theater in Japan. He believed that scripts should be written by intellectuals and that if Japanese plays were more sophisticated, the theaters in turn would become sophisticated places for social interaction. Then in the midst of the so-called Rokumeikan period, the government believed that the group could be useful in treaty and trade negotiations with foreign countries and a number people influential in political and economic circles, such as Ito Hirobumi, Inoue Kaoru, Saionji Kinmochi, and Shibusawa Eichi, thus joined the group.

Suematsu made a series of specific and rather radical proposals to improve plays performed in Japanese theaters. In his book Engeki Kairyo Iken he proposed that theaters should be three-storied buildings made of stone and brick and be equipped with chairs. Tearooms where people could drink tea and alcohol during the interval, he said, should be replaced with break rooms, while runways were not necessary. He also proposed that narrations by gidayu be discontinued and that nothing should be sold. Western music should be played to relax the audience during the interval rather than the shamisen or tsuzumi. In regard to training actresses and writing scripts and scenarios, his proposals seemed endless.

While Suematsu's proposals were not realized, Fukuchi Ochi and others built Kabukiza in such a way as to improve the quality of plays performed in Japanese theaters, but through a more practical approach. Ochi made strenuous efforts to provide better scripts. Ichikawa Danjuro Ⅸ was particularly eager to improve plays, and, in an age in which people were very eager to improve almost anything, better performances were highly promoted. It was noted, however, that, "Academic critics are just argumentative about improvement, but ... those engaged in traditional Japanese plays treated these critics with utter contempt." (Meiji Hyakuwa written by Shinoda Kozo.) Okamoto Kido recalled that no great improvements or progress was made, saying, "Plays welcomed by the intellectual class would not attract the general public. Accordingly, plays on family troubles and thieves continued to be performed."

Subsequently, following the end of the Russo-Japanese War, a great number of overseas VIPs started visiting Japan. However, top officials here found it difficult to find suitable meeting and entertainment places. Accordingly, debate on the improvement of theater flared again and the idea of constructing a national theater soon developed. Some dominant figures theoretically expressed their ideas about the construction, including Saito Shinsaku (the younger brother of Takayama Chogyu) in his book titled Kokuritsu Gekijo to Kinenzo too Kensetsuseyo, and Ueda Bin in his book titled Kokuritsu Gekijo no Hanashi. Others also expressed their opinions, including an article published in The Daily Yomiuri dated October 1905, which said: "Distinguished guests from foreign countries will be stunned at strange dances performed in Koyokan, after being served with unpalatable Japanese dishes at the high-class Japanese-style restaurant in Tokyo."

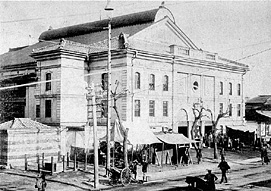

It was against this backdrop that Teikoku Gekijo was constructed. Although it was not a national theater, it was a Western, Renaissance-style building, which Suematsu and others who insisted that Japanese theater needed improving, were longing for. (For information on Teikoku Gekijo, please refer to the separate article)

Reference

- The Daily Yomiuri【YB-41】

- Ihara Toshio, Kabukinenpyo, Iwanami Shoten, 1962 【774.032-I157k-K】

- Ueda Bin, "Kokuristugekijo no Hanashi" Bungei Kowa, Kanao Bunendo, 1907 【74-360】

- Okamoto Kido, Lamp no Shitanite (Iwanami Bunko), Iwanami Shoten, 1993 【KD487-E43】

- Okamoto Kido, Yamada Hajime (ed.), Fuzoku Meiji Tokyo Monogatari (Kawade Bunko), Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 1987 【KH465-E2】

- Kaburaki Kiyotaka, Yamada Hajime (ed.), Meiji no Tokyo (Iwanami Bunko), Iwanami Shoten, 1989 【KC19-E9】

- Shinoda Kozo, Meiji Hyakuwa, Vol. 2 (Iwanami Bunko), Iwanami Shoten, 1996 【GB415-G7】

- Suematsu Kencho, Engeki Kairyo Iken, Bungakusha, 1886 【25-286】

- Mine Takashi, Teikoku Gekijo Kaimaku (Chuko Shinsho), Chuokoronsha, 1996 【KD11-G10】

- Yamamoto Shogetsu, Meiji Seso Hyakuwa(Chuko Bunko), Revised ed. Chuokoronshinsha, 2005 【GB415-H47】

- Kabukiza Hyakunenshi Honbunhen, Vol.1, Shochiku, 1993 【KD11-E21】

- Engeki Hyakka Daijiten, Heibonsha, 1960-62 【770.33-E742-W】

- Kokushi Daijiten, Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 1979-97 【GB8-60】