The start of meisho-e (pictures of famous places)

The establishment of meisho (famous places)

Meisho were long ago called "nadokoro" (a different reading of "meisho") and were words for particularly famous areas written about as uta makura (place names appearing in classical Japanese poetry) in Waka poetry and other noted places. Meisho that appeared in literature, historical events, legends and folklore, as well as historic sites were nadokoro, and even included some places that didn't really exist. However with the coming of the Edo Period travel became more common, and the term came to be used to specify actual places that could be visited, leading to the establishment of meisho.

Political conditions stabilized during the Edo Period, and sankin-kotai (a daimyo's alternate-year residence in Edo) led to the development of roads, lodging facilities, means of transportation, etc., in addition progression of currency circulation allowed for more convenient and safe travel. During this peaceful period, the common people also acquired more economic power. Public travel began to be more active from the Kyoho Era (1716-36) with a travel boom occurring during the Bunka and Bunsei Eras (1804-30).

Ise Sangu Ryakuzu (Sketch of pilgrimages to Ise Shrine) ![]()

by Hiroshige, printed by Ebisuya Shoshichi in 1855 <Call no. : 寄別1-9-1-4>

In those days, the most popular destination was the Ise Shrine. This was because at the time, the common people could not travel freely, but were only allowed to travel for reasons of faith such as worship and pilgrimages. However, most of the people who visited Ise from Edo would then travel to Kyoto or Osaka after visiting the shrine and visited meisho and historical sites, and would enjoy plays, shopping districts and sightseeing.

"Ise sangu daijingu he mo chotto yori" (Also a small side trip to the Grand Shrine when visiting Ise")

This senryu poem clearly shows although the main purpose of their trip was supposed to be visiting the shrine, it was actually just a "small" part of the trip and the main purpose was actually sightseeing.

In addition, the common people's entertainment grew from just further travels to outings for cherry blossom viewing and enjoying the cool evenings within the town and nearby suburbs. These types of entertainment were originally the province of the samurai class, however they came to be adopted and enjoyed by the townspeople as well. Because Edo was a new city, made in 1590 when Tokugawa Ieyasu moved to the prefecture, there weren't many traditional meisho. However, a number of spots became meisho one after the other as the city grew and developed, and the city soon became a major sightseeing city.

As travel and outings became more popular with the common people, these meisho came to be better known, conveyed by mouth from person to person. From the Meireki Era (1655-58), a variety of texts which introduced the various places were published and became popular, including meisho-ki (illustrated guidebooks for pilgrims and travelers as well as for the general reader), traveler's journals, geographical descriptions, travelogues, etc. (Column Edo guidebooks) This resulted in the spread of the meisho throughout the country and became established.

Development of ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) techniques

The themes of the early ukiyo-e were mainly licensed pleasure quarters (prostitutes) and plays (actors). Scenery is thought to have begun to be used as a theme for ukiyo-e towards the end of the Kyoho Era (1716-1735). Up until this point, scenery was mainly only painted as background or for composition in wood block prints of traditional black ink landscape paintings.

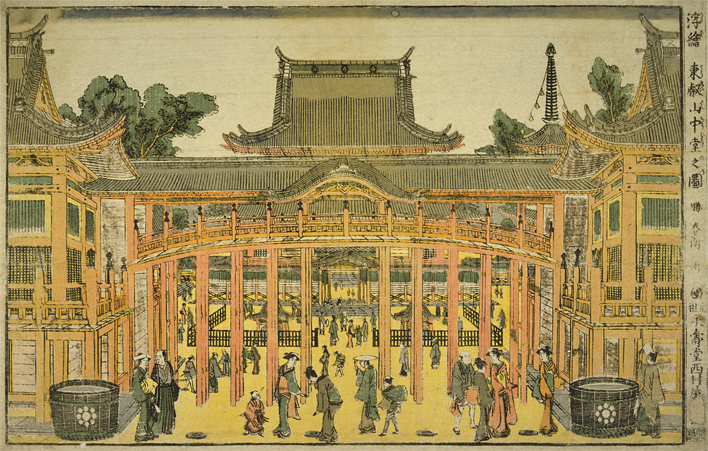

One of the factors that led to the development of ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) landscapes was the introduction of the technique of perspective from the West. In the West, perspective was seen in the art of ancient Greece, however, it was mostly unused in Japanese art. In 1720, the 8th shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune loosened the order to ban the import of the foreign books, and the approval of the import of texts which were not related to Christianity served as an opportunity for the import to Japan of copperplate prints which made use of perspective theory and perspective in their composition. Perspective was then adopted in ukiyo-e and around 1739 pictures called "uki-e" (perspective pictures) began to appear and became popular.

Uki-e are pictures which emphasize a sense of depth and distance and were also called "kubomi-e" (hollow concave pictures) because of the way the distant scenery seemed to sink inwards. Major early uki-e artists included Okumura Masanobu (1686-1764) and the first generation Torii Kiyotada (birth and death dates unknown). In the early uki-e, pillars, ceilings and other elements were used to draw interior spaces (stages, drawing rooms) and buildings for which it was easier to incorporate perspective. Thereafter, the perspective techniques used in uki-e were improved by Utagawa Toyoharu (1735-1814), and more vast scenery such as mountains, rivers and oceans, began to be depicted, which had a major effect on the later development of landscapes.

Uki-e Toeizan Chudo no Zu (Mt. Toei-zan Central Plaza Picture) ![]()

by Katsu Shunro <Call no. : 寄別2-1-1-6>

In 1765, the printing of multi-colored ukiyo-e prints, mainly from Suzuki Harunobu, began and came to be called "nishiki-e (brocade pictures), due to the beautiful brocade-like hues. Up until then, most had been hand colored or 2-3 color prints, however with nishiki-e, 7-8 color printing was possible, greatly expanding the range of expression. This also led to the gradual development of more precise carving, graded color-printing and other printing techniques, allowing for the depiction of scenery and nature.

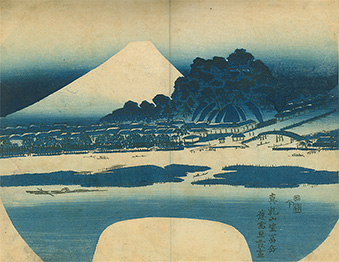

Matsuchiyama kara Fugaku o nozomu (ai-zuri uchiwa-e) ![]()

by Tanka in [1833] <Call no. : 寄別7-4-2-6>

There were also changes in colors. The chemical pigment bero-ai (Berlin blue) was imported from the West, and began to be used in ukiyo-e from 1829. Bero-ai was a corruption of the name Berlin blue, which referred to Prussian blue. Bero-ai was invented by the German alchemist Johann Konrad Dippel (1673-1734) in 1704. In ukiyo-e, pigments made from the leaves of Chinese indigo were used, however only a very dark Prussian blue could be produced. Bero-ai produced good coloring, and could produce vivid colors, so its use allowed for expression of deep colors for oceans, rivers, the sky, etc. In 1830, ai-zuri (blue prints) style uchiwa-e (fan paintings) by Keisai Eisen, which used only contrasting shades of bero-ai, led to a surge in popularity of ai-zuri. 10 of Katsushika Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji were painted as ai-zuri and were very popular.

With this desire for travel and excursions by people, Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji and Utagawa Hiroshige's Fifty-three Stations of Tokaido were major hits. This led to meisho-e becoming a major genre of nishiki-e along with yakusha-e (actor prints) and bijin-e (print depicting beautiful women).

While it was said that travel was popular among the common people, it was still an era where most could only go on one such trip in their lives, if at all, so the Meisho-e which allowed people to more easily access some of the enjoyment of travel were extremely popular. It seems likely that people often viewed the nishiki-e as either a chance to view places they had never seen before, or as a way to lose themselves in the memory of a long ago trip.

Bibliography

- Hanyu Fuyuka, Edo meisho no seiritsu, seijukukatei ni kansuru kenkyu (Toshi keikakuronshu No.39 2004.10 p.115-120 <Call no. : Z3-992>)

- Ikegami Mayumi, Edo shomin no shinko to koraku, Doseisha, 2002 <Call no. : GD15-G13>

- Kobayashi Tadashi and Okubo Jun'ichi, Ukiyo-e no kansho kiso chishiki, Shibundo, 1994 <Call no. : KC172-E56>

- Smith, Henry DeWitt, Ukiyo-e ni okeru "Blue kakumei"(Ukiyo-e geijutsu No.128 1998.7 p.3-26 <Call no. : Z11-304>)